Archive

Gift Section

|

Got In laws? Get Indigestion Give Indiscriminately God! Incense Give Imaginatively? Grab It Get I It |

Frozen Thoughts? Finding Trinkets? Festive Trap? Frank’s Turn Forget That! From This For Tuppence |

3 for2

That’ll Do!

by Irene Brown

Dealing With Family and Friends

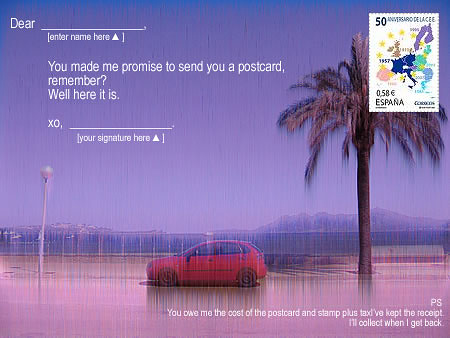

When she thought of economy, she thought of social exchange theory — the idea that relationships are based on give and take; our feelings about relationships rest on perceptions of the balance between what we get out of them and what we put in. Usually, she wouldn’t have put her thoughts on paper, but this time she did — as concisely as possible, using the medium of the postcard which embodies economy of words (few) and form (small).

(Click on postcard to see larger version)

The small print, barely legible, made her think of the papers she’d signed that morning — typical legalistic transaction papers that detailed who gave how much for what: 23 Euro for temporary ownership of a compact car, fully insured.

Now for a tobacco shop, to get some stamps. Driving down the bay road, she scanned for the yellow sign, partly wishing she wouldn’t find one. Yet, there it was. Exactly four minutes later it was done — the stamp bought, glued to the card, the card on the way, like her again, and her thoughts. Small print, she concluded, is invisible with family and friends, even though it’s always part of the subtext; unstated and implicit yet ever-present, like a PS suggesting an afterthought of little importance — which, in social exchange, really isn’t.

by Karyn Eisler and Dorothee Lang

Download the MP3 (reading by Karyn)

Let Go

The goal now, as you see it, is to get home. The front has come in early. Wind jars the car on the asphalt. The rain comes hard and cold, makes flashlight beams of streetlights. It’s hard to drive, but it’s also hard to steer. Maybe one too many boilermakers with buddies at Nightlite. But who can blame you, even if you had been good about staying on the wagon for three months, since Liza left.

She hasn’t sent as much as a postcard. You watch her credit card charges on your bill, then throw it away. You tell yourself you won’t check the mail again until it’s time for the unemployment checks to come. Four years in the sausage room at Don’s Deluxe Meats didn’t mean a thing in the end. No gratitude, no severance pay. Let go without any ceremony at all.

If you can just get home, you’ll be okay. The streets are filling with water. You imagine you are the captain of a boat in strong currents. But you do find a way to stop at Discount Package Store for two fifths of cheap bourbon. That will get you through tonight, and maybe more.

At last you reach your street, hit the curb twice, coming to a stop in front of your dark house. You stagger up the walk, and you can hear them bark. They watch you through the window. The welcome wagon. They have waited, the faithful boys, Lewis and Clark.

You feed them and let them run outside in the rain. They come in, shake off the wet night, and lie down at your feet. You gulp the bourbon and watch them. First one, then the other, falls asleep. Let go. Begin dog dreams.

You think that dreaming is best in a warm, dry room. Better still if outside the darkness howls. What do they dream about? Old hunts, saliva, instinct. In a lurching pack under a grey dawn sky, waiting for a waterfowl kill.

Or do they dream of being human, inside a warm house on a wild night. Sitting back, plastered, watching the dogs dream.

Economy of the Untamable

1

I know the road

hangs by a thread

swiftly moss, sudden trees

pieces of sound

come like fish when called

say rain, say spiral

eyes murmur

so it is

breath can’t be simple, can it

everydayness of afternoon

breath can’t find

can’t be simple, can it

roots on a slant

get used to loneliness

salt, hemispheres, glass

break into sky

taste extends

as avalanche

quiet network of hieroglyphs

2

Night seasons

I speak a streaming wind

thrash, throw myself at corners

far off, hidden, lurking

under this lid of cloth, this flap of lawn

how hard to say

only what’s inside

every step sinks

myriad bees

widen my mouth

do you hear me

awake at the bottom of the glass

3

Why do I

speak hard things

days consume

let the sea

why do I

almost dwell in silence

speak hard things

alone—eyes

easy isn’t simple

without the sea

noise melts into hills

4

Any minute

is there then a world

night speck

what distracts me

is there then

a world

are these grains or dust

a world

how far can I fling

myself from sleep

how far

any minute

myself from sleep

effort coils

without face

without road

neither grain nor dust

any minute

a world

5

Underwater thickens sky

let me lie here

alphabetize myself

whatever you do, please, don’t come and go

whatever you do, please

thoughts ridge

unending

what if part of me all of me

into matchbooks

underwater thickens

part of me all of me

can’t stay like this

here the absence

here the drums

by Jane Rice

Need

Tell me this poem doesn’t exist on paper and needs

the red movement of a mouth.

Tell me you are in the poem.

Your lips wrap every word,

brown packaging, mailed first-class,

for the trip across the country between us.

Tell me we’ll never say this poem.

Tell me we can ride through

today in a winter of quiet.

The only papers in my wallet are lists —

groceries and wishes. Tell me these things

fill the blank flat space in its folds.

Don’t speak of emptiness or silence.

Emptiness hitched across the country,

silence filled the country.

by Gregory Stapp

No Diminishing Returns

We talk fifty miles over wire, a mile

for each year since our eyes touched.

Legends still vibrate in your voice, fables,

story of a stray star, Atlantis provoked,

burst meadow beyond the hill, bedding down,

a tree counting the darkness, flower in a field

of rye. I remember a winter clean as salt,

memorialized snow banks, foreign country

of a couch thickly green and awkward

as landed amphibian, a blue wool skirt

of accordion pleats I blew smoke into,

my ear on its blue sky listening to stars

inside, eyes closed, mouth opened,

stretching, reaching, turning corners.

by Tom Sheehan

underneath is snow

“we were thinking of our bodies as snowsuits instead, thinking this would make us pretty.” (Click on photos to see larger versions.)

February Day Trip

That we didn’t, after all,

go anywhere that day

hardly matters, looking back.

We discussed it in each other’s arms,

weathervaned the state,

considered lakes, obscure museums,

unknown and nearby towns,

and mind-explored some routes

to be later found, or not,

on the toast-distracted map

unfolded over what

was fast becoming lunch.

Next there were the tasks

we ought to do before

we started out:

the laundry,

email,

something we’d forgot.

All the while the sun,

which always plans ahead,

rolled on its grudging round,

Time’s chariot.

And yet,

we traveled, looking back.

by Susan Donnelly

What the Forest Said

Tell me.

Which part?

All of it. Any of it. Just—something vivid.

–

I was walking.

Yes?

And there were two deer.

Whitetails?

Yes, whitetails, flashing alarm. They heard the dog. I didn’t tell him; he was looking for a good stick, something nice to throw. The deer flipped their tails and danced away. I could see reflections of yellow beech leaves in the eye of one of them, turned toward me: she was that close.

–

Tell me another.

I don’t know what to tell you.

Please.

–

Bobwhites.

What?

Six or seven of them, exploding from the underbrush with wing-beats so loud I ducked. The dog ran so fast he ran right out of the orange t-shirt I put on him to differentiate him from bear.

Bear?

It’s bear season. They’re shooting bears.

Oh.

He treed them.

The bears?

The bobwhites. They were furious.

I bet he was proud.

Very proud.

–

You’re going to leave, aren’t you.

Yes.

Soon?

Probably. There isn’t much left.

There is. There could be—

Shhhhh.

–

One more. Tell me one more.

–

Once I walked into the woods and there was only one way: further in. I walked and walked, and I was fierce and beautiful and brave and resourceful and I had many adventures, but I was getting tired. Very tired. I couldn’t walk any more, finally; I couldn’t be fierce and beautiful and resourceful and brave any more. Also? I was bored with myself. With all of it. I dug a fire-pit, lined it with stones. I gathered wood, and made a fire. I was so hungry, but I had nothing to eat and I was too tired to do anything else, so I sat by the fire and watched the flames. I figured I’d probably die of starvation eventually, but really, the flames felt good and I couldn’t think what else to do. A stag came out of the forest, walked right up to the edge of the fire across from me. We looked at each other for a long time, and I thought: how beautiful. After a while, he lay down across the fire and split himself open, his blood steaming in the coals. I ate his flesh, and was restored.

That didn’t happen.

No?

No.

–

–

I saw a peregrine eat a bat today.

Yeah?

–

–

You’re going, aren’t you.

I’m going.

–

I have an idea.

Yeah?

When I go, just look away.

–

Okay.

–

–

Now? Should I look away now?

The Supper at Emmaus

just over,

Caravaggio’s Christ

stood in the Tube

dressed in jeans

and shapeless jumper

holding a jacket

for his girl.

by Irene Brown

Note: I wrote this poem in 2005 after having been to the exhibition Caravaggio: The Final Years at the National Gallery in London which included his painting The Supper at Emmaus. This year, I came across and read the Salley Vickers novel, The Other Side of You, which featured the painting in its theme. I saw it again drawn in chalk on a Florence pavement by a Texan artist, Kelly Borsheim, and her students.