Archive

The Rules

Christopher Woods lives in Houston and Chappell Hill, Texas. His online gallery is Moonbird Hill Arts.

The Word

He liked his girl

innocent, and when on her knees at twelve

she refused to pray, said

she was too tired, didn’t believe anyway,

then told him what the boy across the street had whispered,

that fuck that lit up his mouth

what his squat fingers had done

clamping the front of her shirt like a crab,

her father backed her into a closet,

unbuckled his belt and slammed it

hard across her bare ass

but it took so long for her to scream

that when she did that word escaped

fueled his arm, and her mother ran

upstairs to stop him but

stopped herself instead when she saw his face

and remembered the taste of his belt on her flesh,

watched the strap land again and again

until blood fell and he stepped back

turned from his wife in tears, the girl

gasping the same bad word until

cool cloths and dreams did their work.

Apologies became denials and

grew into a forest of thorns

nobody could see

and the girl didn’t know if

what she remembered was real

or a bad dream because she had swallowed

the thorns and they flowered

inside like a secret she never told

even when she married, and one night

when her husband, backing her down to

keep her in line with a few gut punches

where the bruises wouldn’t show

unclamped the brass buckle from his jeans

and jerked the leather belt from beneath his belly

to teach her to keep her goddamned mouth

shut, to get her to screw when he

wanted her to, that closet door

unhinged like a jaw and thorns made stone,

honed to diamond points, gleamed through,

and she ran to the kitchen, grabbed

the butcher knife from its slit in the block

and caught him, slashed the soft pink swell

of his gut, screaming

fuck fuck fuck in her head

but making no sound at all.

Susan Roney-O’Brien teaches, reads for The Worcester Review, and writes. Her work has appeared in Calyx, Slipstream, Yankee, Prairie Schooner, Diner, Concrete Wolf, Beloit Poetry Journal, The Christian Science Monitor, Margin, and other magazines. She has won the Worcester County Poetry Association Contest, the William and Kingman Page Poetry Book Award for her chapbook, Farmwife, and the New England Association of Teachers of English “Poet of the Year” award.

Maledictus Requiescat

Oh may your casket smother you because

You won’t be buried dead. And may you wake

In ground-chill dark, 6 feet below, mistake

Your ability to free yourself, sores

Sprouting from your fingertips as you try

To pry, to claw, to push your panicked way

Out of your prescribed resting place. I pray

And will that you won’t drop dead too fast. I

Will that you suffer. I will your breath to

Come in hard-laboured oxygen-starved waves:

Short and incomplete. I want all the graves

Around to shudder as you suck the few

Final molecules of breathable air

Into your lungs, alone, alone, down there.

Juleigh Howard Hobson is a formalist poet, essayist and short fiction writer. A former finalist for The Morton Marr Prize, she has had poems nominated for both the Pushcart and the Best of the Net Award. Her poetry has appeared or shall appear in Mobius, The Lyric, The Raintown Review, Candelabrum, Poem Revised (Marion Street Press), Return of The Raven (HorrorBound) and scores of other venues. Her chapbook, Sommer And Other Poems, was published by RavensHalla Arts, who will be publishing her forthcoming chapbook, The Cycle of Nine, later on this year.

Dear Brain

by Muriel Karr

(lavish love letter, written in the hope of ending

severe migraines; the ruse didn’t work)

Beloved brain, precious seat-of-emotion amygdala,

how hard you have worked to make me who I am. O pons,

much-praised cerebellum; fourth ventricle, observed

in my atlas of human anatomy; nuclei and fiber bundles,

long may ye wave, though I may not have mentioned you before.

I live in gratitude, despite any moaning, for your complexities,

dear brain. Your pathways, your receptors; how you integrate

motor signals. Medulla oblongata, hippocampus, colliculi;

occipital lobe, gray and white matter, mammillary bodies:

have I told you lately how much I love you?

I love to speak your name, though I consider you

not Broca’s, but mine, dear brain. O cranial nerves,

did my switch of handedness from left to right

disturb you? Does all flow as it should, in your cerebral

aqueduct? I want, even cherish, your over-excitable cells.

Tell me what food I should feed you: I will provide.

You will be massaged; caressed. Iced, if needed, when vessels

expand with blood; I will shrink what ails you; comfort

with cool hands. You afford me, dear brain, a peerless mind

connecting dots as no other. Let me count the ways.

Download the podcast

Muriel Karr was born in Lowell, Massachusetts on Mother’s Day in 1945. Her two books of poetry are Toward Dawn (2002) and Shape of Pear (1996), both published by Bellowing Ark Press.

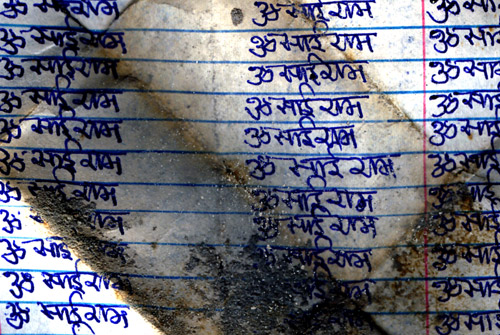

“Om Sai Ram” A Thousand Times

Click on image to see a larger version.

Over twenty years ago my mother brought from India samples of the sacred ash, vibhuti.

Ash is all that remains after wood is burnt away. And in a similarly manner, God as imperishable Truth is that which remains when all names and forms are dissolved.

Sathya Sai Baba, considered by many to be an incarnation of the divine, is fond of materializing vibhuti for his devotees. This ash is carefully wrapped in small paper packets constructed from sheets of paper upon which devotees have inscribed Om Sai Ram — a thousand times, ten thousand times — in their longing to find God.

This image is of one such packet that has been in my dresser drawer all these years.

While not a follower of Baba, I do regard the vibhuti as something of a modern day miracle not unlike blood appearing on the crucifix or tears from a Madonna.

Here’s a link to my mother’s kitchen where vibhuti is materializing from Sai Baba’s picture.

Patricia Bralley lives in Atlanta and blogs at Seeing For My Self.

Cuss Club

Randy and his mom always moved to new places. This was the third place since I became friends with Randy. It was a townhouse where we could sneak out onto the granular slant of the roof and see the lights of Chattanooga. The gush of water from the spout, the clang of pots and pans in the sink, and light from the kitchen would signal if his mom was coming and we needed to dodge back into his bedroom. He held up his hand when the kitchen noise hushed and the light flipped off.

You wanna stay over next Friday? We can go out in the woods and cuss.

Next Friday was such a long time from that Sunday, so I just said yeah. He shushed me when we heard the door to his room open.

Randy, his mom recited. Then the door shut.

I been learning from my cousins from Nashville. They taught me, he splayed his fingers, five new ones. We can go say em in the woods.

I was through the window as soon as he rose. Just as his foot touched the carpeting, the door swung open and his mom asked, Where you been Randy?

We was hiding under the bed, ma. Tricked you.

Randy, I was looking for you. Gil’s gotta go home now. Gil, did you call your parents?

No, ma’am.

Well, I think you need to call them.

Yes, ma’am.

***

Both my parents came to pick me up.

Did you have fun?

I shrugged my shoulders.

I hope you had fun. Miss Byson just keeps moving further and further away from us. We had to cut through the city from the theater. It’s quicker, but you have to go through some bad parts of town.

What Randy said came from my mouth as, Hey mom can I please stay the night with Randy next Friday?

They both stayed silent while we passed houses with wooden windows and people huddled around a loud car. We sped up and cuffed a bump in the road. I could see a long line of street lights, all the color of pee.

Gilly, I just said—

Mom, don’t call me Gilly.

Say please. Show some manners when you talk to your mother, said my dad.

Gil, she continued, I just finished telling you it’s a long drive for you to come out to see Randy. Why can’t he come out to our house?

I don’t know, I said.

Maybe his mom is tired after work. Maybe she can’t afford the gas, my dad answered.

My mom gripped his arm. Gilly—I mean, Gil? You wanna ask him over to our house?

But we don’t have woods.

Yes we do. We have the woods out by the golf course. What used to be Shiners’ Gully.

I don’t know if they’ll be safe in there, Burt.

Well, said my dad, Lord knows where they’re going when they’re out here. It’s just a bunch of apartment complexes, he mumbled.

Okay I get it, my mom said. How come you wanna go to Randy’s on Friday and you already decided to ask, my mom said glancing at me.

My dad’s deep voice echoed. I said, I’m gonna show him Shiners’ Gully. Can I ask Brandon and Terry?

My mom only shook her head and my dad, turning onto the right fork of the road, said, Well we’re out of it.

***

I stood far away from Randy. My mom would have taken us to Papa Joe’s pizza and the arcade but he wanted to go in the woods. His mom never took us out. Brandon hissed and shook his head. Terry watched Brandon and I kicked the bottom step.

My mom smiled and climbed back up the stairs. I heard her walking around up there through the ceiling.

Y’all wanna go out there? Y’all ready?

Ready for what, said Brandon.

You’ll see, said Randy tucking his feet into his slipons.

Brandon snickered and we filed out the front door and across the street. The woods were not far and after cutting through a short stretch of trees we dropped down the slope. Shiners’ Gully was only fifteen minutes across. But it was steep. Jagged logs had washed up along the banks and nested against one another.

Brandon was the first to cuss. Shit, he said when he slipped and landed on his butt in the mud. Randy just stared at him with a solid gaze, his eyes like black-eyed peas. I waited for him to cuss. He only twitched his nose like he was excited by a smell, then bounded to the gully bed.

The ground was sludge and gave off a swamp stench. My last two steps had caused my feet to sink under past the ankle. I just stood stuck there until I heard Randy laughing. You look like you wanna cuss, he said.

Man I’m not going down there, said Brandon.

C’mon now, said Randy. Let’s cuss.

That looks nasty down there, said Terry.

You wanna know one, asked Randy. He flung his arms and rocked on his heels, squishing the mud I had fallen in.

What, said Brandon.

You wanna learn some cuss words, asked Randy.

Cusses, said Brandon. That’s why you brought us out here?

Randy’s eyes narrowed and his mouth stayed open, like it was ready for anything to come out. I thought I could see his freckles vibrating. Shit, he said. Then he said, Fucker.

You just brought us out here so you could cuss? Why didn’t you just cuss at home?

Randy still smiled but his voice was softer and his breath was heavy. Cause a mom might hear us, he half-asked half-said.

Are you retarded, asked Terry.

Shit. Fuck, said Randy. C’mon! I know shit, fuck, ass, cunt, and bastard.

Do you know what any of those mean?

Randy chewed a couple times and said, My cousins taught em to me.

I know what all of them mean, said Brandon.

So, said Randy.

So, you’re stupid. I know what they mean—you don’t.

So, said Randy. I was gonna teach em to Gil. Gil don’t know em.

Brandon’s icy eyes fixed on me and he set his hands on his hips. Terry pinched his nose and shook his head. You don’t know curses, Gil?

Fuck, I said. Shit, I said. Fuck you, I said aimed at Randy. Ass, I said. Fuck you cunt, I said. Then, You bastard. Fuck you, bastard.

Bet he knows what that one means, said Terry behind Brandon as if he was whispering.

Randy’s fists balled. His jaw grinded. His eyes pooled.

***

I only saw Randy once more after that day. I was hurrying along the tile floor of the mall searching for Brandon and Terry who had played a game where they yelped and covered their noses and mouths like I stunk that bad, then ran away and hid. I had to find them.

A growl from behind made me flip around. It was Randy. He was glaring at me with a grin across his face. His upper lip was curling, baring his teeth. He still hadn’t learned to curse.

Fuck. You’re a fuck. You’re a fucking shitty dick. You’re a fucking bitch. Bitch.

Once he started using new words, I turned around and kept walking. He cursed louder and followed. I noticed people wincing, eyeing him from the stores. Fucker. Fuck you. Shit.

There was one word he would never use. I kept searching for my friends. I rounded corners and stepped out onto the bridge to the parking deck. He broke off at the glass doors and watched me, glaring at me while I tried to ignore him. Finally, I forgot he was there.

Ian Singleton was born in southeast Michigan and has lived in Alabama and now in Massachusetts. He attends Emerson College in Boston as an MFA student and works as a librarian at Harvard University. He teaches in the PEN Prison Writing Program. He translated and published a story by Rainer Maria Rilke in Knock. A story of his appears in Conte Online.

St Joseph of Cupertino. 9/18

Maybe it’s the lighthead — wanting

in mental capacity so that when Joseph studies

for a test, he focuses on one item only. Prays

for his examiners to ask that question. Flying,

however, comes easily, happens trancing

on God, involuntary; one minute he’s

with his fellow Franciscans, the next he’s taken off. It happens

first on the order’s feast day, then with increasing

frequency. He can’t stop, poor empty-

handed priest, no matter the ascending rank of those who order

him not to make a spectacle of himself.

Exiled by the pope to Assisi then to one commune and the next, he goes dry,

ordered not to speak to anyone other

than his bishop, until the last mass, Assumption Day, overcome by happiness, he lifts off.

Download the podcast

Wendy Vardaman (website) has a Ph.D. in English from University of Pennsylvania. Co-editor of the Wisconsin poetry journal Verse Wisconsin (formerly Free Verse), her poems, reviews, and interviews have appeared widely, and her first collection of poetry, Obstructed View (Fireweed Press), has just been published. She works for a youth theater, The Young Shakespeare Players.

Go My Uncle and Fetch the Bride

by Jane Rice

1.

Under the road

a floor

black heat kidnaps the sun

and the desert planes land, land, land

soldiers float dreams

in shallow-

dug holes

as if they need

only width of shoulders

length: with boots

as if they scoop

fading light

to keep it

world of stories below

spring from the sea

2.

Who remembers

the tree

the garden

words make faces

something

lies in wait

side street

of trembling

labyrinth

arms itself

with branches

stream trickles

no wider

than a wrist

who

remembers

pebbles

hand’s gray face

nostrils on fire

shaken

eyes echo

each voice

of a candle

sings to the tree

3.

Little thing

like distance

soldiering a nest

of stones

smoke fans gray

and gray

fans smoke

fluke of breath

revives

sky of crushed

tilts wandering

the word earth

limited to land

amounts

to flight

charcoal tree

against the mountain

as are pronouns for those

not in the room

one plus one equals and

distinct

not interchangeable

ears weep

even if eyes

refuse

dust of nameless inks

remember the tree all green

*

Note: A 16th century poem, know as L’Chah Dodi, is sung at Friday night services to welcome the sabbath bride. There are many variations on the tune and numerous translations. The literal translation of the first line is Go my uncle towards bride. I heard it translated as Go my uncle and fetch the bride. I loved that translation much better than another version I had read: Beloved, come to meet the bride (or) Let’s go, my friend, towards the bride. This summer I was studying prayer-book Hebrew as part of my process of converting to Judaism. We were studying possessives, hence an explanation of “my” uncle.

Jane Rice lives in San Francisco and pursues her interests in poetry, art and art history. Please visit Propolis Press for information about her letterpress chapbook entitled Portrait Sitters.

Ceremony: the Opening of the Mouth

by Alex Cigale

May my heart be with me in the house of hearts

May it be given back to me among the living

May it toll and mete out a steady measure

Though daily I am seen rolling my past

like a ball of dung in front of my face

with pincer-like paws — the resurrection —

I am born anew in the rising sun

singing the random code of combinations

keys to the kingdom of everlasting life

Arise ye to the boats you wise boatmen

to the recitation of parts — masts sails oars

rudders — mechanisms of struggle for control

Commit to memory the many names

and the many gates of the doorkeepers

internal strictures and structures of soul

Great power resides in appellations

under ancient laws a slave had no name

and thus no function as a legal person

Forbidden to label compelled to invent —

physical body the shadow the full title —

panoply of names that death may not find me

Alex Cigale’s poems have recently appeared in The Cafe, Colorado, Global City, Green Mountains and North American reviews, Drunken Boat, Hanging Loose, McSweeney’s, and Zoland Poetry. Other work can be found online at The Adirondack Review, Babel Fruit, Big Bridge, The Externalist [PDF], nthposition, The Potomac Journal, Quarter After Eight, The Salt River Review, and Synaesthetic. His translations from the Russian can be found in Crossing Centuries: the New Generation in Russian Poetry and in The Manhattan and St. Ann’s reviews. He was born in Chernovtsy, Ukraine and lives in New York City.

Lung Ta (wind words)

“It’s simple,” he explained. “You put up the flags in a high place — and the wind carries their mantras into all pervading spaces that are in need of them.”

Dorothee Lang edits the BluePrintReview, an experimental online journal, and currently is into collaborative works. Her work has recently appeared in LITnIMAGE, Counterexample Poetics, Otoliths and Wheelhouse. For more about her, visit her at blueprint21.de.