Archive

Two Romanian poems by O. Nimigean

translated by Chris Tanasescu and Martin Woodside

nu-ţi garantează nimeni nimic

întâi treci prin foc focul nu e aşa cum îl ţii tu minte

un caras auriu cu aripi lungi înotând în sobă

sau alintându-se în iarbă (ochii lui fără pleoape

te-au urmărit o vreme te mai privesc şi acum)

focul e altfel nu se vede nu îl

vezi când arde curg de pe tine sudoare şi

zgură arde cu cuvinte incendiază

fantasmele provoacă metamorfoze groteşti vei

trăi nopţi în care statuile se schimonosesc stelele

fixe se zbat în zig-zag-uri lumina însăşi se umple de

pete hohotind ca o hienă vei trăi zile pline de fum

şi de mucuri zilele mutului

nu-ţi garantează nimeni că nu vei crăpa

că nu te vei întoarce bâţâindu-te

nuâţi garantează nimeni nimic e pe bune

no guarantees

first you walk through the fire fire not as you remember

a golden carp with long fins swimming in the stove

or prancing in the grass (its lidless eyes

have followed you awhile follow you still)

the fire is not like that not visible you don’t

see it when it burns sweat and dross flow

from you burns the words sets

phantasms on fire triggers grotesque metamorphoses you will

live through nights with statues distorted fixed

stars zig-zagging the light itself fills with laughing

spots like a hyena you shall live days full of smoke

and cigarette butts

no guarantees that you won’t croak

that you won’t return trembling

no guarantees from anyone about anything. This is for keeps.

*

din străinătate

gol într-o noapte încinsă

undeva la marginea germaniei

fosta fermă tace în întuneric

viermii moi se preling în sus şi-n jos

pe punga de gunoi bio de sub chiuvetă

îi privesc fără scârbă

şi constat că moartea

nu mă mai înspăimântă

poate e o trufie

ce va fi pusă cândva

crâncen la încercare

dar moartea

nu mă mai înspăimântă

mă înspăimântă cumplit

respiraţia mea liniştită

pulsul

odaia noaptea românia

căreia-i simt de departe

mirosul dulceag de stârv

moartea—nu

from abroad

naked on a scorching night

somewhere in far off Germany

one time farm keeps quiet in the dark

soft worms streaming up and down

around the recycled trash bag under the sink

I watch them without disgust

and notice that death

no longer scares me

maybe that pride

will someday be

bitterly put to the test

but death

no longer scares me

what scares me completely

my calm breath

the pulse

the room at night Romania

where I sense at a distance

a cloying corpse smell.

death—no

O. Nimigean is a poet, novelist, and critic — one of the major voices of contemporary Romanian literature. His style is praised for its freshness, versatility and chameleonic variety, while his wide range of registers and forms span pastiche, satire, profane experiments with reshaping the sonnet, ballad, love-song, and elegy. Scathing political sarcasm shortly follows intimately harrowing confession, while jocular (self-) irony goes hand in hand with deep heart-felt genuineness in a poetry that speaks with both strong urgency and thoughtful serenity.

Martin Woodside is a writer and translator whose chapbook of poems, Stationary Landscapes, came out in 2009 (Pudding House Press). His translations of contemporary Romanian poets will be featured in a forthcoming feature section from Poetry International and in an anthology from Calypso Editions. He spent 2009-10 on a Fulbright Fellowship in Romania, researching/translating contemporary Romanian poets.

Chris Tanasescu (blog) is a Romanian poet, academic, critic, and translator whose work has appeared in Romanian and international anthologies and publications. He is author of four collections of poetry, recipient of a number of international awards and leader of the acclaimed poetry performance / action painting / rock band Margento. He is spending 2010-11 as a Fulbright visiting professor at San Diego State University in California, researching poetries and communities.

Two poems from the Plant Kingdom

The Birthday Roses

from The Book of the Red King

Their fine green feet are pointed, hovering in the vase,

Close together as if in love but slanting outward,

Their petal perfection, their fine-grained velvet red

Is wonderfully marred as if by sgraffito—

Is there an inner layer of rot or ebony?

Dragon-toothed and tongued, the sepals of the calyx

Make up a star tightly cupping the corolla.

In time the sepals arch and thrust the widening

Whorls of petals upward: loosened wombs of fragrance.

Glasshouse dryads, the roses hold out helpless arms

That backroom florists filled with stems of babies’ breath:

The Fool drinks in the red that tends toward black, the sage

Of paddle leaves, and cranes his head to see the stars

Half-hidden underneath. I see that you are twelve,

He says aloud, as if they might be listening.

Perhaps you are the twelve months of the zodiac,

Virgins, water-bearers, archers with sheath of thorns.

Perhaps you are the twelve apostles of good news.

Perhaps you are a twelve-string lute of silences.

Or else you are the winter’s Twelve Days of Christmas

That in the cold and blackness rise to flowering.

No, I know what you are, the Fool tells the flowers,

For days or months are one, and so are blooming you…

The one who stumbled from his bed of rotten leaves.

You are my rose-red heart, my rose-red birthday hat,

The blossom in my mind: you are the Red King’s Fool.

*

Wielding the Tree Finder

Do you ramble the ground—are you a tree and yet a forest,

does your great bulk blossom in one night

like an elephant singing a love-song to the moon,

do you transform to a reservoir for water and stars,

do you grow hollow for whistling,

do you become an ossuary,

do you hold African mummies in your heart,

are you baobab?

Were you sacred to healers and priests who haunted oak groves,

golden shoulder pins on their woven garments,

your parasite branches in their hands

—the raspberry girl slaughtered, seeds between her teeth—

were you sharpened to a Norseman’s spearpoint,

did your mischief kill a god, fairest of the Aesir,

do you draw warmth of kisses to an orb of leaves,

are you mistletoe?

Are the rosy pastors and the bulbuls feasting on your seeds,

are you red and hairy like Esau,

are your flowers good in bowls of curried pottage,

are you a tree of red silk cotton,

bombax malabarica?

Were you a thousand scented pillars

around the forecourt of an emperor,

are you malleable in the whittler’s palm,

are you swooning-pale and infant-smooth,

are you a parasite tethered to roots of others,

are you sandalwood?

Are you loose-tethered, a yielder of leaves to wind,

are you a sender-out of roots, are you clone,

is a forest of your kind one sentience,

and in fall are you quivering yellow,

boreal, afflicted with melancholy,

a breather of mists and cold,

are you quaking aspen?

Do your flowers steam with fragrance as the heat increases,

do the chrysomelids rut within your clutch of petals,

do your blossoms shatter as the beetles copulate,

are you Amazonian—are you annona sericea?

Are you a kingdom, are you castles in the air,

are you a garden of Babylon in mist,

are your branches colonies of dreaming epiphytes,

are the flicking tails of lizards lost inside your cities,

are you flying above the prayers of the Maori,

are you kauri, the tree that must forgive?

Were you as dense and black as mythic thrones of Hades,

were you strong, were you midnight ripped in lengths,

were you foretelling gleams—Victoria’s jet beads—

were you heavier than the fat man’s coffin,

were you Pharoah’s favorite chair,

are you ebony?

Are you dawn redwood or frangipani,

are you whistle thorn or cannonball,

are you linden, myrtle, jacaranda,

are you sourwood or silverbell,

are you a branch of good and evil,

are you the lemurs’ Ravenala,

are you Yggdrasil, axis of nine worlds,

are you a cross whose branches reach forever,

are you water-tapping, cloud-catching, sun-devouring,

are you leaf, are you branch, are you root, are you tree?

Marly Youmans (website, blog) is the author of six novels, including The Wolf Pit (Farrar, Straus & Giroux/The Michael Shaara Award) and Val/Orson, which was set among the tree sitters of California’s redwoods, as well as a collection of poetry. Currently forthcoming are three novels: Glimmerglass and Maze of Blood from P. S. Publishing (UK) and A Death at the White Camellia Orphanage (winner of the Ferrol Sams Award/Mercer University Press), and three books of poetry: The Throne of Psyche from Mercer University Press, The Foliate Head from Stanza Press (UK), and Thaliad from Phoenicia Publishing (Montreal).

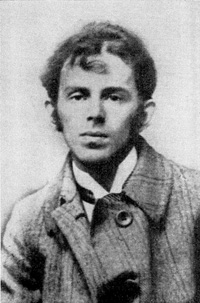

Three poems by Osip Mandelstam

translated by Stephen Dodson

Есть иволги в лесах, и гласных долгота

В тонических стихах единственная мера.

Но только раз в году бывает разлита

В природе длительность, как в метрике Гомера.

Как бы цезурою зияет этот день:

Уже с утра покой и трудные длинноты,

Волы на пастбище, и золотая лень

Из тростника извлечь богатство целой ноты.

*

In the woods are orioles: the length of vowels

in tonic verses is the only measure.

But only once each year does nature lavish out

lagniappe duration, as in Homer’s metrics.

Like a caesura yawns this day; since morning

there have been peace and arduous longueurs,

oxen in pastures, and a golden languor

to draw out of a reed a whole note’s richness.

* * *

Возьми на радость из моих ладоней

Немного солнца и немного меда,

Как нам велели пчелы Персефоны.

Не отвязать неприкрепленной лодки,

Не услыхать в меха обутой тени,

Не превозмочь в дремучей жизни страха.

Нам остаются только поцелуи,

Мохнатые, как маленькие пчелы,

Что умирают, вылетев из улья.

Они шуршат в прозрачных дебрях ночи,

Их родина — дремучий лес Тайгета,

Их пища — время, медуница, мята.

Возьми ж на радость дикий мой подарок,

Невзрачное сухое ожерелье

Из мертвых пчел, мед превративших в солнце.

*

Take—for the sake of joy—out of my palms

a little sunlight and a little honey,

as we were told to by Persephone’s bees.

You can’t untie a boat that isn’t moored,

nor can you hear a shadow shod in fur,

nor—in this dense life—overpower fear.

The only thing that’s left to us is kisses:

fuzzy kisses, like the little bees

who die in midair, flying from their hive.

They rustle in the night’s transparent thickets,

their homeland the dense forest of Taygetus,

their food: time, pulmonaria, mint…

Here, take—for the sake of joy—my wild gift,

this necklace, dry and unattractive,

of dead bees who turned honey into sun.

* * *

Бессонница. Гомер. Тугие паруса.

Я список кораблей прочел до середины:

Сей длинный выводок, сей поезд журавлиный,

Что над Элладою когда-то поднялся.

Как журавлиный клин в чужие рубежи—

На головах царей божественная пена—

Куда плывете вы? Когда бы не Елена,

Что Троя вам одна, ахейские мужи?

И море, и Гомер — всё движется любовью.

Кого же слушать мне? И вот Гомер молчит,

И море черное, витийствуя, шумит

И с тяжким грохотом подходит к изголовью.

*

Insomnia. Homer. Taut sails.

To midpoint have I read the catalog of ships:

That long, that drawn-out brood, those cranes, a crane procession

That over Hellas rose how many years ago,

Cranes like a wedge of cranes aimed at an alien shore—

A godly foam spread out upon the heads of kings—

Where are you sailing to? If Helen were not there,

What would Troy be to you, mere Troy, Achaean men?

Both Homer and the sea—everything moves by love.

Who shall I listen to? Homer is silent now,

And a black sea, a noisy orator, resounds,

And with a grinding crash comes up to the bed’s head.

Osip Mandelstam is universally considered one of the greatest poets of the twentieth century. He was born in 1891, grievously offended Joseph Stalin through his insistence on truth-telling, and died in 1938 on his way to a prison camp. These three poems are from his early, classical period; they are among his most famous. The translator has not attempted to reproduce the rhymes but has tried to provide an equivalent sonic richness, and the rhythms have been carried across as accurately as possible.

Stephen Dodson was born in 1951 into a Foreign Service family; he has seen many cities and learned many languages. Having given up on an attempt to join academia as a linguist, he earns his living as a freelance copyeditor and since 2002 has written the blog Languagehat, where language and poetry, among other things, are discussed. He has both hats and cats.

Los Angeles and Hong Kong: two poems

by Floyd Cheung

At Queen’s Bakery, Los Angeles

In my mind’s Cantonese,

my favorite pastry sounds

like the words I know for

assassinate ride horse:

Saat keh mah—

syllables spliced together

from Chinese gangster films.

The worker points and says,

You mean rice puffs?

I nod but think of the hero shot dead,

his rickshaw driver oblivious.

On Jogging in Hong Kong with My Daughter

Five years ago, I jogged alone—

my first visit to the land of my birth

after a long absence.

I noted the tai chi practitioners’ slow elegance,

toddlers’ first steps,

old folks sitting still,

other joggers apparently not noticing me—

a rare sensation

in Western Massachusetts,

where neighbors make assumptions

about where I’m from,

what I do, who I am.

Today, my daughter jogs with me.

She notes the birds,

asks what kind they are.

I don’t know their species,

but we conclude

that they are Chinese.

*

NOTE: This poem originally appeared in The Aurorean.

Floyd Cheung was born in Hong Kong and grew up in Las Vegas. He teaches at Smith College in Northampton, Massachusetts. His poems have appeared in the Apple Valley Review, the Bryant Literary Review, the Naugatuck River Review, Rhino, and other journals.

Reclamations

by Anna Dickie

Lenten Rose

Click on image to see a larger version.

This is a photograph of an origami flower made from an old gardening book. The flower was a gift; I don’t know who made it. But I’m grateful for the opportunity to participate in a chain of translation: from idea to paper, paper to form and form to a solarised photograph.

*

Hill’s Vest-Pocket Flemish-English/English-Flemish Dictionary

Published, London 1917

A spent volume,

bound in frayed vermilion.

Left behind on bare boards.

Inside, on a flyleaf:

The Briton Abroad Series,

Indispensable to every traveller.

I thumb what must have been

Great Uncle John’s lexicon.

Eye picking out an alphabet

that lips can barely form:

Aanbruisen, to rush on, to foam

Bemind, beloved

Cipres, m. Cypress

Dampig, vapourous,

Eeheid, f. unit, unity

Flikken, to patch, to mend

Geklep, n. tolling, peel (of bells)

Hunkeren, to long for

Insmeren, to grease

Kankerbloem, f. wild poppy

Leeuwerik, m. lark

Maan, f. moon

Nok, f. ridge,

Opwekken, to rouse

Pel, f. shell

Raap, f. turnip

Snipperkoek, m. gingerbread with orange peel

Toon, m. tune, tone, voice

Uur, n. hour

Vlasbaard, m. (fig.) beardless boy

Wapenstilstand, m. truce, armistice

Zaad, n. seed

Anna Dickie lives near Edinburgh in Scotland. She started writing poetry in her late forties and has been placed in a number of competitions. Born in West Africa and educated in Scotland, she is married with one university-aged son. Anna has had two pamphlets published, Peeling Onion and Heart Notes, published in 2008 by Calder Wood Press.

In 2009 she co-edited the Economy issue of qarrtsiluni. She performs with two other Scottish women poets in a group called Poetrio.

Max Ernst

by Marie-Claire Bancquart, from Avec la mort quartier d’orange entre les dents

translated by Wendeline A. Hardenberg

Du papier émeri, laissé brut et coupé de fentes.

Le peintre

a mis dedans

en cage

des oiseaux.

Il les a mis en cale

en décalage

sur la toile

les a engeôlés.

Les oiseaux réussissent à glisser quelques plumes multicolores à

travers les barreaux,

ils implorent, ils forcent.

C’est un carré de quatre centimètres sur quatre, dans la grande toile peinte en

couleur aurore.

Mais on ne voit que ce devant de cage, aux reflets coruscants.

*

A bit of emery paper, left rough and cracking.

The painter

has placed inside,

caged,

some birds.

He has put them in the hold

out of step

on the canvas

jailed them.

The birds manage to slip a few multicolored feathers

between the bars,

they beseech, they break out.

It’s a four centimeter square, within the large canvas painted in

rosy gold.

But you see only the front of this cage, and its coruscating sheen.

Marie-Claire Bancquart (b. 1932) is a prolific and prize-winning French poet, novelist, essayist, and critic, as well as a Professor Emeritus of French literature at the Sorbonne (Université de Paris-IV). Her most recent book of poems, Explorer l’incertain, was published by Amourier in 2010.

Wendeline A. Hardenberg received a dual Masters degree in Comparative Literature and Library Science as well as a Certificate of Literary Translation from Indiana University Bloomington. She is currently pursuing a dual career as a librarian and a translator. Some of her translations of Marie-Claire Bancquart’s poetry have previously appeared in Ezra: An Online Journal of Literary Translation [PDF] and Ozone Park Journal, and are forthcoming in The Dirty Goat.

Insulation

The man came in with a long black hose. I was elbow-deep in soap-water, and the baby was in her chair. “Mmm, mmm,” she was saying, “Elmo, Elmo.” Lucky Charms flew. More men came in after the first, stomping their dirty brown boots on the Welcome square, then walking onto the triangle of sunlight made by the open door.

“Who are they?” I yelled to my husband. He was only on the other side of the kitchen island but he might as well have been on the other side of the world because before we knew it, the men were drilling holes into the walls, and he couldn’t hear me. I couldn’t even hear me. Baby’s lips were moving. “More, more,” she was saying, but her words were drowned out by the thrum of saw into drywall.

I tore a packet of oatmeal and poured it into the bowl. The blades of the saws shone, and the muscles in the first man’s forearm popped; I imagined how blue the outside sky must be, all that light pouring in. My husband held up two fingers. I held up two too. “Peace,” I mouthed. I smiled. It seemed a perfect day for all to be forgiven. He shook his head, pointed to the oatmeal. “2,” he pressed into the air again. I tore open another packet and tapped it into the bowl.

The floor shook with sound. The neighbors must have thought the world was coming to an end; or that we were finally just tearing into each other — a couple of wild-eyed cats spinning in cartoon-dust; or maybe they thought that our home would rise right out off the block, shoot into the sky, rocket its way right into the depths of outer space. I imagined them running out into the street: Dmitri with his horse-hair bow and Gail with her bum-hip and JJ with his beard and his two boys, how they’d stand there watching us arc into the sky — me and husband and baby soaring into the heart of the closest black hole.

My husband held the spoon in his mouth and scribbled blue ink onto an old hotel pad. It always surprised me to see his handwriting — the closed o’s, stumpy f’s. Soundproofing, the note read.

“What?” I asked, and he underlined the word twice.

Baby had her hands over her ears. “No, no, no,” her mouth said.

My husband moved in Irish-Spring-close. I felt his breath on my neck and then he yelled in my ear. “They’re pumping shit into the walls.” He pointed at the word again.

“Oh,” I said. “Okay.” I gave a thumbs-up.

So no one can hear us? I wrote.

So we can’t hear them, he wrote back.

The drywall dust was beginning to settle, and the room grew quiet again. The man lifted his long black hose. “Sorry about all the racket,” he said. “Think of this as the last noise you’ll ever be subjected to.”

We laughed, and my husband tightened his tie, and baby blew him kisses, and I think that I was yammering about vitamins — about the Fish Oil and the D and how bad the burps are but how important it all is — but deep inside I was panicking; deep inside, I was terrified of what the night would bring — without the whine of Dmitri’s cello, or the click-click-click of Gail’s cane, or JJ’s sweet boys with their lilting, twinkling stars — of how silent it would be, of how lonely I would be in its silence.

Nicole Callihan’s poems, stories and essays have appeared or are forthcoming in Painted Bride Quarterly, Salt Hill, Washington Square, New York Quarterly, cream city review, and La Petite Zine. She was a finalist for the Iowa Review’s Award for Literary Nonfiction, and has most recently been named as Notable Reading for Best American Nonrequired Reading. She lives in Brooklyn and teaches at New York University, as well as in schools and hospitals throughout New York City.

Three Modern Iranian Poets

translated by Sholeh Wolpé

I See the Sea…

by Shams Langroodi

I see the sea shrink

then shrink again

until it fits in the palm of my hand.

And I

hear the sound of flying fish,

the dead sailors’ cough, the burning whales,

the shivering mermaids, the horses and the wind,

the sea’s white curls,

and the drowned strangers who have forgotten their human voice.

I see

the sea

shrink

then shrink even more

the oars’ hopeless beats,

the foam-circled boats,

the frozen shadows,

the salt encrusted stores,

the disheveled hopeless left on the shore…

Oh what strange mystery,

the sea!

I see your purple fingers

in the beakers of the dead,

and the shoulders of the wind

drenched with your mouth’s sweat,

and I see your bitter joy.

I see

the sea

shrink,

then shrink again,

and I

float farther

from the invisible shore.

Where is this familiar boat

whose oars’ solemn sound mingles

with the rain carrying us?

*

Shams Langroodi was born in 1951, in Langrood, a coastal town edging on the Caspian Sea. In 1981, he was arrested as a political activist and served a six month sentence due to his opposition. He has published six collections of poetry, including Notes for a Warden Nightingale and The Hidden Celebrations, a novel, a play, and an anthology of Iranian poetry. His four volume history of modern Iranian poetry, Analytical History of the New Poetry, was banned in Iran for many years.

My Hands Tremble Yet Again — A Soliloquy

by Sheida Mohammadi

When

the sky

pulls its coat tight over its head, and

the rain keeps nagging, and

my pink doll

misses the sun…

I become weary of you.

When

the teacup on the table

is a crow starring at me

my throat begins to taste like caw caw.

Black-beaked clock

until dawn

black-beaked clock

till dawn

Clock…

The telephone goes mad with silence,

and I, go blue with you.

Aromas quit the house.

Happiness ditches me.

And the dirty laundry

keep spinning, spinning…

My mother’s silver spoons drift and dash in the kitchen. Un-ironed shirts

lounge over cactus trees. I put on your dirty socks and waltz

with your black striped pants. The house spins around this washing

machine, round my head. Dirty dishes play games on the kitchen floor.

I yell at the flower pots and blow out the candles. Happy birthday to me!

I bang on the typewriter and am drenched in your hands’ dried up sweat.

I change the TV channel to coax a yawn into my swollen lids.

I hate the pink nail polish bottle I found on the piano.

Black-beaked clock

until dawn

black-beaked clock

till dawn

Clock…

Now

the sycamore’s yellow bluffs

and highway 118 …

do not pass me by.

Strawberries,

like your expressions of love,

make me want to barf.

This month,

that month,

I come to hate you.

I hate you.

*

Sheida Mohamadi was born in Tehran, Iran, and received her B.A. in Persian Language and Literature from Tehran University in 1999. Author of three books, she was recognized as one of the most notable contemporary Persian writers of 2010 by the Encyclopedia Britannica. Her third book, Aks-e Fowri-ye Eshqbazi (The Snapshot of Making Love) was published in 2007. Her Poems have been translated into various languages, including English, French, Turkish, Kurdish and Swedish.

Blood’s Voice

by Mohsen Emadi

If one day flood brings in a sad panther

and a shrine’s door,

if they sew up a shirt with the panther’s skin,

make a necklace with his teeth,

I know that whoever puts on the shirt

will disappear,

and whoever wears the necklace

would be obliged to carry

her own head under her arms.

I take the shrine’s door

install it on the threshold

of my house. It creaks open

to a circle of women,

heads on knees,

caressing their own hair.

Outside, body-less heads

surround a fire with songs.

I don’t recognize my own voice

and the door closes and opens

to the rhythm of the words I grunt.

It is raining.

A unclothed woman knocks on the door.

She carries a boat on her back.

I greet her between the panther’s roar

and the door’s groans.

Silently she unloads her boat in a corner,

climbs in and falls asleep.

The house is in water.

Water carries away corpses of women,

it carries away the door,

and my voice.

We paddle.

We row looking for the voice.

My legacy is a door through which

when a woman enters or leaves

my voice cracks,

and the house drowns in that alien sound.

Each time my bed is a boat

to attract the nudity of a woman.

A women’s nakedness is silent.

It is wet.

I uproot the door,

plant it on my rooftop.

The wind blows.

Guns appear on the threshold of the door.

They point themselves at my throat.

The wind blows

and a thousand wounded panthers

leap out from my mouth.

I am naked.

An unclothed woman,

wet,

draws herself out from among the guns,

kisses the door,

kneels before me.

Panthers leap out from her hair.

I caress your hair.

The door will shut,

voices and winds will pound on the door.

I will not open.

And the lost voice of the man

will become blood,

will flood through the cracks

and mingling with the rain

that will come pouring,

it will flow through the city’s gutters and veins.

I kiss you

and my blood leaps out with every breath,

out from my throat.

It becomes my voice.

You are silent.

You speak inside me.

There’s no one on the rooftop.

I stand there, collect all the photographs

the shirts, the photos of a thousand hands holding guns,

the portraits of women’s heads

and the narrow stream of blood

that flows on the paper’s edge.

I light a match,

throw into fire the shirts and the papers.

The fire has your shape.

I want to touch your hair.

I reach for you

and become a poet.

I pick up my pen

and blood flows from my hand.

The lines are your hair,

in every line a panther roars.

**

On the balcony

I fill my childhood cradle with soil,

plant roses inside it.

I water the roses,

rock the cradle.

The city is silent.

*

Mohsen Emadi was born in Sari, Iran in 1976. He is the author of a collection of poetry, translated into Spanish and published in Spain. He is the founder and manager of Ahmad Shamlu’s official website and The house of world poets website, a Persian anthology of world poetry that includes more than 100 modern poets.

Sholeh Wolpé (website) is the author of Rooftops of Tehran, The Scar Saloon, and Sin: Selected Poems of Forugh Farrokhzad for which she was awarded the Lois Roth Persian Translation Prize in 2010. Sholeh is a regional editor of Tablet & Pen: Literary Landscapes from the Modern Middle East edited by Reza Aslan (Norton), the guest editor of Atlanta Review (2010 Iran issue), and the editor of an upcoming anthology of Iranian poetry, The Forbidden: Poems from Iran and its exiles, due out from the University of Michigan State Press this year. Sholeh’s poems, translations, essays and reviews have appeared in scores of literary journals, periodicals and anthologies worldwide, and have been translated into several languages.

Nineteen years ago this summer

by Andy P.

BillRueben’s Inside, Ann Rueben glanced |

RuebenAndy had his I was just thankful no need to say |

AnnBill and Dad working in silence every polite word |

AndyDad had hair Dad’s hands reaching out, |

Andy P. is a recent graduate of St. Olaf College in Northfield, Minnesota with a degree in vocal music education. He currently works as a Tour Actor/Director with Missoula Children’s Theatre. Andy spends his free time writing music and poetry.

My Soul Speaks in Three Languages

tanka from English, to Spanish and Iluko

…tri-lingual in English, Spanish and Iluko, the language (dialect) I was born with but hardly spoke and never wrote with from my early teens, when I moved to the city for university, until two years ago when it reawoke, first in a Yahoo group and later in a website I stumbled upon. Iluko, a dialect of the northern-most edge of the Philippine archipelago, traces its roots to Austronesian languages. Like most of the major Philippine dialects (87 of them not counting sub-tongues), Iluko tends to be metaphorical and thus poetic. Melded in its spirit is Spanish, introduced by the colonizers 400 years ago — not only as a language but a culture and a soul, both of which we, Filipinos but specifically Ilokanos, can hardly discern on the conscious level. English sort of flowed in only in the past century, easily so because the Spaniards had by then changed our alphabet from what was believed to be Sanskrit to Roman. I believe that when I write I do so from three cultures uniquely one, uniquely mine. But I began explaining all three when one day, I took a break from the haiku that I usually post in my personal blog and in reply to someone who got to my blog, searching for the word willow in Pilipino, I wrote as follows.

Citing the absence of a Pilipino (or Iluko) word for willow tree demonstrates how language is deeply entrenched in culture: the totality of one’s being layered over by influences of earth, air, water, living things, language whispered, sung, murmured, chanted, stated, shouted, screamed, written for one to read under fluorescent light, Coleman light-flood, moonlight, candle light — how we whine and laugh and cuddle up wordless or word-full, with what flowers we offer our sighs, what trees we carve arrow-pierced hearts into, from what looming shadows we scamper away, what wings we shoot down, from what edges of cliffs we plunge off to get to our dreams.

In languages like mine born of life, a borrowed word — just one, say cry or sob — fails to bring out how anug-og in Iluko pictures a bent figure broken in grief, shaking with spasms of pain, sobbing an animal cry that escapes from the depth of caves. Or saning-i, one of my favorite words, portrays someone — usually a woman in a dark corner, splayed on the floor, propped on the wall, the neckline of her dress dropped, the hem of her dress carelessly gathered — deeply hurt, flayed in spirit, melting in helplessness, too enfeebled to even scream or sob, simply shaking with sorrow in what sounds like staccato coughing broken by wet sniffles. Saning-i is also the cry of a child suffering from chronic hunger pain, as in children whipped into living skeletons due to kwashiorkor, or a baby burning with fever.

Language is as mysterious as the spirit, indeed.

No, dear friend who’s asking if there is a translation of willow tree in Pilipino, there’s none I’m aware of. None of our trees have looked as sorrowful, sometimes sinister — under Philippine skies that stars perforate, crowns of mangoes and some other trees sparkle. No, nothing that does not belong can be a match, can be translated.

*

In these three tanka, I used all three languages my soul speaks with. The English translations are mine, as are the Spanish, but edited by Sr. Javier Galvan y Guijo, director of Instituto Cervantes in Oran, Algeria. The Spanish translations are more or less word-for-word except for particularities of Spanish in terms of number agreement.

1.

among the willows

the wind sometimes listens

to whispers

steals from ripples of the lake

our secret sighs

entre los sauces

el viento a veces oye

los susurros

roba de las ondas del lago

nuestros suspiros secretos

kadagiti kaykayo

no dadduma agan-aningas ti angin

kadagiti ar-arasaas

mangtakaw iti apges ti luok

dagiti limed a sen-senaayta

NOTES: In Iluko, there are no definite prepositions; kadigiti in the poem indicates “among.” Also, the present tense in the word “listen(s)” serves well enough to actively refer to the action of listening, but in Iluko is not enough, hence the use of the participle, as in agan-aningas (listening), compounding the first syllable. Also, the plural form in Iluko is not a suffix, but similar to the way a participle is formed, is made by compounding the first syllable, as in sen-senaayta (sighs). Again, while in both Spanish and English, “ours” is another word, it is a suffix, -ta, as in sen-sennaayta (whispers) in Iluko.

2.

any which way

leaves and sparrows flutter

even fall in the wind

so unlike downcast hearts

rooted among stones

de cualquier forma

las hojas y los gorriones revolotean

incluso los lleva el viento

a diferencia de los corazónes abatidos

arraigado entre las piedras

uray kasano

agampayag latta dagiti bulbulong ken bulilising

matnagda pay ketdi babaen ti angin

saan a kas dagiti nalimdo a puspuso

a nagramut kadigiti batbato

NOTE: The adverbial clause in the first line, “any which way,” translates in Iluko as uray kasano. The word uray has no equivalent in English and Spanish, though in this line, it is used to mean “whichever.” Also, the simple present tense in the verb agampayagda (they flutter) works here because it has a pair in matnagda (they fall) in the next line. “In the wind” would be directly translated as ti angin, but in Iluko, it makes better sense with the use of babaen (because) in the third line. Notice the suffix -da in the verb matnagda, cited above to indicate “them,” referring to the bulbulong (leaves) and bulilising (sparrows). In the last line, the past tense — “rooted” — is indicated with the prefix nag-.

3.

fallen leaf in the garden

only the wind can lift it up

or leave it to its fate

without the wind for thoughts

destiny ends each day

la hoja caida en el jardin

sólamente el viento lo puede levantar

o seguira su destino

si no viento por los pensamientos

estos destinos se fini cada dia

tinnag a bulong iti hardin

ti angin laeng ti makaipalais

wenno makaibati iti kapaayanna

no awan ti angin iti likud dagiti pampanunot

malpas ti gasgasat iti inaldaw

NOTES: The modal auxiliary verb “can” is a prefix makai-, as in makaiplais (can lift it up) and makaibati (leave it) in Iluko. Also, notice how agreement of numbers and verbs in Iluko follows the Spanish rule: los pensamientos/estos destinos translate as pampanunot (“thoughts,” with compounded first syllable) and gasgasat (destiny). To use the plural, “destinies,” in the English version to me would be awkward.

Alegria Imperial has had forty years of writing and media work, public relations and marketing from staff to managerial positions in government, educational and cultural institutions in the Philippines before she started to write poetry and fiction. She has won a few awards, and had been published in literary journals in print and online, including The Cortland Review, poeticdiversity.org, and LYNX. She now lives in Vancouver, BC. Read her essays on Philippine topics at Filipineses and her haiku at jornales.