Archive

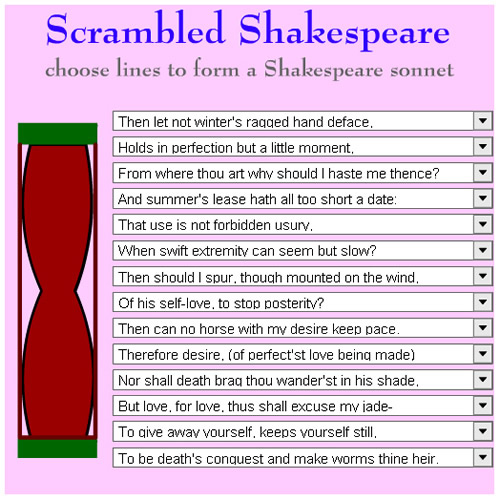

Scrambled Shakespeare

by Millie Niss

Click through to Flash animation

Millie Niss (Sporkworld) was a poet and new media artist who died at age 36 from complications of H1N1 in November 2009. She received a Classical education via Columbia University’s “Lit Hum” program and her earlier studies for the Baccalaureat section C (Math/Physics), Lycee Pierre D’Ailly, Compiegne, France. Her poetry and new media work has been exhibited at Harvard’s Dudley House “Errors and Contradictions” exhibit as well as SCOPE 2006. Her work appears on or is reviewed in many print and online publications, including: Iowa Review on the Web (with Martha Deed), Museum of the Essential and Beyond, dvblog, Unlikelystories, Hyperliterature Exchange, and Vispo.com. Her haiku generator (2009) was published on Logolalia. Her video, “I am the very model of a Psychopharmacologist,” won the People’s Choice Award at the Digital Arts Festival, Buffalo, NY and is found online at the Perpetual Art Machine.

Egil’s Lament

(after Egil’s Saga)

Egil was the firesap in the birch tree,

the raven, his ebony wings’ glint,

his croak that opened the underworld—

Egil who walks on two widow-sticks now.

Egil was the meadhorn running amber rivers,

the wolves’ fur rank and steaming beneath fir trees

groaning with snow: Egil now frosted and feeble

needing the old flame.

Egil was the snarl, the fang bared

to summon the enemies, set them wrangling.

Now Egil sits by the hearth, dodging the blows of women.

Time passes tediously, no king to aid him.

Egil was the salt spray, the dolphin,

the ship turned into the wind,

Egil clammy-cock, hair grown ashen.

And Egil was the sharp-toothed sea all luck was lost in.

Ann Fisher-Wirth’s third book of poems, Carta Marina, was published by Wings Press in April 2009. Her third chapbook, Slide Shows, was runner-up in the 2008 Finishing Line Chapbook Contest and was released in December 2009. Her poems have appeared widely in journals, online, and in anthologies, including Starting Today: Poems for the First 100 Days, HOW2, and poetryvlog.com. She teaches at the University of Mississippi, and also teaches yoga at Southern Star in Oxford, Mississippi. Until she broke her knee, she was scheduled to teach in Switzerland and give readings in Sweden this spring.

So soft his neck, so distant from the thought of stone

So soft his neck, so distant from the thought of stone,

I am appalled to see it pass into a stone.

That night swam for so long and slipped out of my hands.

Tonight it is as clear as fossil in the stone.

I come from a small country of large alterations,

where stone erects no memory for passing stone.

Somebody is fucking somebody in a corner.

Everybody juts as if released from stone.

Why have you come to kill this mutant, strong young man?

Hack off my head, and I will still turn flesh to stone.

There is a slippery slope in things that lie down flat.

In all coming and going speeds there is a stone.

He is not dead, I tell you, he is merely sleeping.

The rest of you move back. Jee, roll away the stone.

Jee Leong Koh is the author of two books of poems, Payday Loans and Equal to the Earth (Bench Press). His poems have appeared in Best New Poets (University of Virginia Press) and Best Gay Poetry (A Midsummer’s Night Press), and in LA Review, Drunken Boat and PN Review, among other journals. Born in Singapore, he lives in New York City, and blogs at Song of a Reformed Headhunter.

Ten Discourses After Jalal al-Din Rumi

by Alex Cigale

These words are for people in need of words.

The heaven and earth indeed are like words.

A hundred thousand wild beasts together

is man. God kneaded the clay forty days.

So long as you perceive pain and regret.

*

Water that recognizes water, clay’s

inclination towards clay. A fault in

your brother is a bigger fault in yourself,

disgust with yourself expressed at others.

All our desires are the desire for God.

*

The animal soul is your enemy.

Violence; in that fist are raisins. When

the prophet spilled blood he must have been wrong.

Your love for Lailah is like a drawn sword.

Intelligence and lust, that which is loved.

*

Endure the tyranny of women for

the sake of children. Life is a garment

to ward off the cold. Thus you must enter

this union, the prison of the body.

Look to the body you know within your life.

*

Speech is a piece of flesh. The hand can speak,

the world is the resurrection. Metaphors

are the forms of God come forth from the sea,

the recollections of the other world.

Neither to the beginning nor the end.

*

There is no more shameful occupation

than poetry. The heart is a free world.

I and there is nobody other than I.

Each day your love for work will grow greater.

Understanding of this is not understanding.

*

Many pens, one loftier than another.

The pens of God. Human activity,

the profit and the loss. The body too

is principle. Yet you know not your own self.

Each one of us has a Jesus inside.

*

Attention is respect. Mongrel affairs,

the body of prayer, supplication and

the unconscious memory of God. We

come into the world with a particular

task. The one thing, the task performed by man.

*

Scholar and prince, for such are the social

relations of a man of God. Like the

sun that turns stones into rubies your trade

is giving. We learn in order to give.

May you bring forth the living from the dead.

*

Thought without word, hidden. Why speak? The one

we have appointed only as a trial.

Them as many, man as one, a great trial.

The true friend of faith. Faith, the one true friend.

The human manifestations of God.

Alex Cigale’s poems recently appeared in The Cafe, Colorado, Global City, Green Mountains, and North American reviews, Gargoyle, Hanging Loose, Redactions, Tar River Poetry, 32 Poems, and Zoland Poetry, online in Contrary, Drunken Boat, H_ngm_n, McSweeney’s, and are forthcoming in Many Mountains Moving and St. Petersburg Review. His translations from the Russian can be found in Crossing Centuries: the New Generation in Russian Poetry, in The Manhattan, St. Ann’s, and Yellow Medicine reviews, online in OffCourse, Danse Macabre and Fiera Lingue, and forthcoming in Crab Creek Review and Modern Poetry in Translation. He was born in Chernovsty, Ukraine and lives in New York City.

Mad Hatter’s Tea Party

Click on the photo to see a larger version.

From the composite photography exhibition Down the Rabbit Hole (see the artist’s statement and extended bio), featuring Tama’s daughter Claire. For more coverage of the exhibition, see her blog.

Tama Hochbaum (blog, website) is an artist/photographer living in Chapel Hill, NC. She is represented by George Lawson Gallery in San Francisco.

Molly’s Bloom (in Fade)

by Maureen Egan

He’s been writing some next epic diuretic walkingeatingliquor sexing tome only 10 of 11 and oh no he’s back here for more no not that pacing Odyssean pacing and driving me pounding my bent head aches backed into the chase my feet are wedged quoins killing well wishes at present I’m mad and no out of breath and no no I won’t No.

Maureen Egan is a recovering technical editor who recently discovered the poetic region of the right side of her brain. Her poetry has been published in Other Voices, Black Box, Blue Skies Poetry, dandelion, The New Orphic Review, and Room, among others. She is continually inspired by the west coast’s wildness and its network of wildly gifted poets, including Daniela Elza, Rob Taylor, and Robin Susanto.

Twilight

All the vampires walking through the valley

move west down Ventura Boulevard,

and all the bad boys are standing in the shadows,

all the good girls are home with broken hearts.

—Tom Petty

They walk the mall in packs. Last year it was

covens—groups of girls or boys—

never mixed. In their minds they are walking

slower than the others. They do not go

into any stores. They have no money.

They never speak to each other,

arrive after dark, leave before nine.

The boys go home and touch themselves. The girls

read their book, repeating scenes like spells.

By morning, most discard their capes,

wait at bus stops in their usual uniforms—

jeans, T-shirts, sneakers their parents

might have worn, hand-me-down backpacks full

of textbooks underlined or highlighted

by brothers and sisters graduated

last year, or the year before that. A few

wear their blacks to school, don’t wash their hair, smell

of cloves. Last night one of them climbed a tree

outside the window, a girl, an oak. She

stayed there till dawn, scanning the street.

When she was sure there were no vampires, she climbed

back through her window and went to sleep.

She missed the school bus that morning. All day

she stayed in bed, pretending to be sick.

Celia Lisset Alvarez teaches and writes in Miami, Florida. She has two collections of poetry, Shapeshifting (Spire Press, 2006) and The Stones (Finishing Line Press, 2006). Her work has most recently appeared in Blood Lotus, Fringe, and Fifth Wednesday Journal. She teaches composition, creative, and scientific writing at St. Thomas University.

In Nihilo

When all the creation stories tripped into reverse

the turning point was palpable —

here a red moon, there a tremor in the earth,

as, remote-controlled and speeding,

the original shocks ran backwards.

All shapes and sizes, dozens of them —

retired demiurges, dazed and blinking,

checked each other’s alibis,

their fingernails for blood. And in the south

the forests drifting into smoke.

Sun on a dimmer-switch, soundtrack slurring,

old words lapsed to opposites, as tricksters

revelled in the glossaries of chaos,

smirked as one more creature disappeared.

In the north, the ice melting.

One last person, fully-ribbed,

gathered to a senseless pile of dust.

A thought in a god’s head

slipped his mind:

now a symptom of the amnesia.

Ray Templeton is a Scottish writer and musician living in St. Albans, England. His poetry and short fiction has appeared widely on the web as well as in print, most recently in Eclectica, nthposition and qarrtsiluni. His e-chapbook The Act Of Finding was published in 2009 by Right Hand Pointing. He is a regular contributor to Musical Traditions and a member of the editorial board of Blues & Rhythm magazine.

Nude with Rash

Limited edition digital print, June 2009

Image dimensions: 6 1/2 x 7 1/4 inches; paper: 8 1/2 x 11 inches

Anne-Marie Levine is a poet and painter who lives in New York City. Her work can be seen online at her website, her visual art at Saatchi Online, and her poetry at NYQ Poets.

Frankenstein’s Brother

by Marc Hudson

Frank is driving too fast. “Speed limit,” I say. He takes his foot off the gas and now we’re barely moving. He wears orthopedic shoes. They’re custom made. My dad says they cost eight hundred dollars a pair. The sole on his right foot is about three inches thicker than the sole on his left. That’s because his right leg is shorter than his left. Apparently, he has legs from two different people — don’t ask me why. The doctors say that the fine nerve endings in his hands and feet aren’t as sensitive as they are in you and me. That’s another reason he’s not good at moderating speed — he can’t feel the pedal. It’s the same with the brake — too much or too little. We won’t let him drive downtown. It isn’t fair to the pedestrians. Frankenstein is my brother. My parents adopted him because after I was born they weren’t able have any more kids on their own. It’s sort of a big deal having a brother made of spare parts. JAMA called him a miracle of modern science.

He’s still learning to drive. This was a big step for him. Huge. Our neighbors, the MacPhails gave us their old Buick LeSabre because it has more leg room. It’s a big sloppy car. My parents thought we’d be safer in something big. We’re on our way to my soccer practice. I’m watching out for road kill so that I can distract him if something pops up. Road kill unsettles him. He wants to fix them. Frank once sat for seven hours with a dead squirrel in his hands, weeping. Well, not weeping, really. His tear ducts don’t work. He just scrunches up his face and moans. I hope that our parents don’t die because he’ll never get over it.

“More speed, Frank.” He mumbles and lifts a hand as if to say ‘make up your mind.’ “Ten and two,” I say. Frank ignores me and turns on the radio. “Too loud,” I say. He’s not supposed to have the radio on while he’s driving. It’s a distraction. He likes the worst sort of pop music. And he likes to sing along. The doctor says that singing is good for his vocal cords. It isn’t really singing, though. It’s like trying to reproduce a painting with a single color. Frank is bobbing his head. He doesn’t see the light changing. “Red light, Frank. Frank, red light!” By the time he slams on the brakes we’re half-way through the intersection. He looks at me with his ‘oops’ face, his eyes huge and goofy behind the thick, blocky lenses of his glasses. We’re nearly t-boned by a man in a blue Mustang. The man shouts obscenities and gives us the finger. Frank raises his mismatched hands and makes a series of meaningless squeezing gestures. He doesn’t handle criticism well. The fact that he hasn’t mastered speech only adds to his frustration. “Gas,” I tell him, “gas, Frank.” Frank mashes the gas pedal with his orthopedic platform shoe and we sail through the intersection unscathed. The car is riddled with dings and dents and scratches. I carry a pad in my pocket so that I can leave notes for the people whose cars we hit. The message goes something like this: ‘Dear Sir or Madam. Please forgive the damage to your car. My brother, Frankenstein, is learning how to drive. He is the sum of many parts that do not always function in concert. Please take comfort in the knowledge that he has hit many vehicles besides your own. Regards, Brian.’ I spot Haley Mishbaum from my biology class and turn away from the window so she won’t see me. I hate that I do this. Some of the kids at school call me Frankenstein’s brother, like it’s a bad thing. They don’t get him at all. I can quote complete paragraphs from scientific journals about what an astonishing and promising accomplishment Frank is, but these kids can’t get past the bolts in his neck. Frank slows down as we approach the Panda Den on Lexington. “No,” I tell him. “There’s no time.” Coach is a stickler for punctuality. If I’m late one more time I’ll be sitting on the bench. “Ahnees,” shouts Frank, turning into the lot. He takes up three spaces, which is okay, because it’s the middle of the afternoon and the lot is empty. I go inside and order crab rangoons, no msg. Frank has high blood pressure. Some of this is from the meds. He takes handfuls of pills to keep his body from going to war with itself. “How’s Frank?” Mr. Chen asks. “Good,” I tell him. The car is shaking. We can hear the radio blasting from inside the restaurant, the sound of Frank singing along.

Frank claps his mismatched hands when I return. He purrs as he devours the rangoons. Bits of fried dough dribble from his lips. I turn down the radio. He turns it up. Technically, he’s my older brother, but I’m the responsible one. “We have to go, Frank.” He licks his fingers. I look the other way and try to forget that the fingers he’s licking aren’t really his. He starts the car and backs into a trash can next to the building. I get out and set the can upright, wave to Mr. Chen. I’m not yet late for practice. There’s time for us to make it. Frank catches the edge of the curb on the way out. The car shudders. He remembers to turn right onto Philpon Avenue. He’s getting better at remembering directions. Frank croons, mashes the gas pedal, lays off, mashes, lays off. Our bodies lurch forward and back. I check my watch. Five minutes. We can do it. I reach over the seat and grab my cleats. I peel off my shoes. Frank stops singing. By the time I look up he has already pulled over. I spot the cat on the shoulder — a victim of the morning commute. “No, Frank,” I shout. Too late. He’s already out of the car, lumbering up the road, arms out, wailing.

Marc Hudson’s work has appeared in The Seattle Review. His short story “Timo’s Creations” will be published by Echo Ink Review in August. He writes and builds gardens for other people in southern New Hampshire.