Archive

The Charmed Life

by Susanna Rich

It takes nothing — talent nor courage —

to be a sleeping princess

in a house of glass — Tiffany doves

floating in door lights, gold

-camed windows, panes that mirror

interior lights over outer darkness.

Things break only from others’ use —

etched flutes and tumblers; the crystal

witch’s ball hung to ward off evil;

Murano lamps; silvered walls;

the central vacuum…

Glaziers come, like charioteers,

with ladders and Unrue racks

to unscrew old strike plates, bleed

the furnace, crawl on their bellies

amongst toads and kittens

transparent in the walls. This is living

in the sky, in the full neon of the sun,

glitter of stars, a store of Magic

Ginger Ale — phosphate bubbles

unreleased — the aspic mold of pansies,

the heart-shaped ice cubes for guests

who bear their envy, to the altar

of you… For a spell to be a spell,

it must be broken — the rescuer must be

disguised, the rescued must seem to sleep

in a life of liquid suspense — perfect,

cold — waiting to be shattered…

Download the podcast

Susanna Rich (website) is a 2009 Emmy Award nominee for the poetry she wrote and voice-overed for Craig Lindvahl’s documentary Cobb Field. She is the author of two poetry chapbooks, Television Daddy and The Drive Home (both from Finishing Line Press); the 2008 Featured Poet of Darkling Literary Magazine; and a Fulbright Fellow in Creative Writing. An internationally published poet and prose writer, Susanna tours the one-woman audience-interactive poetry experience Television Daddy, and is in production for The Drive Home (opening in 2010). She is Professor of English and Distinguished Teacher at Kean University in New Jersey, teaching such courses as Emily Dickinson, William Blake, and 20th Century Women Poets.

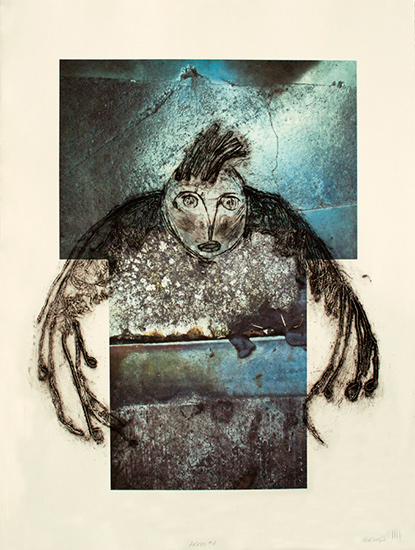

ARKEO 4

Click on image to view a larger version.

ARKEO #4

archival inkjet and collagraph on paper

81 x 61 cm. (32″ x 24″)

For more information on this print, please see Marja-Leena’s blog post about it, and visit her gallery to see the rest of the series.

Marja-Leena Rathje is a Finnish-Canadian artist specializing in printmaking and photography. She is crazy about weathered rocks, prehistoric art and the archaeology of past, present and future. She lives and works near the sea and the mountains of Vancouver and has exhibited widely, both internationally and in her local region.

A Language of One

He uttered

tainted ellipses,

guttural sounds

empty of syllable

so his words

were other than

I had ever heard.

His yaw, jive and

garble mimicked,

it seemed,

a marred parrot.

Seated in the back

corner of the

subway car, he

was in continuous

self-rejoinder,

chortling,

purling, braying.

Everyone else

out of it.

We locked glances

as though at any

moment, madness

might commit fury

and send us

running for our lives.

But the man

paid scant attention

to us as he followed

the thread of his

conversation,

come 2nd Avenue,

out of the car.

Allen C. Fischer, former director of marketing for a nationwide corporation, brings to poetry a background in business. His poems have appeared in Atlanta Review, Indiana Review, The Laurel Review, Poetry, Prairie Schooner, River Styx, and Rattle.

November

by cin salach

Spell for the Undoing of Prayers

Let go the hands that fold me, let go the tongue that tells me

the trees the creek, they know, they will speak me now

Let go the house that holds me, let go the family that calls me

the moon the sun, they know, they will hear me now

Let go the name that follows me, let go the voice that carries me

the ocean the stones, they know, they will sing me now

Let go the sex that begins me, let go the veil that becomes me

the ground the breeze, they know, they will reveal me now

*

I leave my signs of leaving spread neatly across the floor announcing

I’m leaving

to architect my own body

in the smooth ache of arch and bridge the red belly of fly and seed green of water

gold of wind stillness of pine and stone crawl of light.

I’m leaving

to hear my own body answer:

she is a wave, all the rest is negotiable.

cin salach has been performing and publishing in Chicago and around for over 20 years. She is both baffled by and grateful for online submissions of poetry. Actually, she is baffled and grateful by/for most things.

(incantation: ekstatic)

by Jeneva Stone

I have gone back to ground

back to the fine root hairs

that lie along your skin

gone back to ground I have

in hand the world’s blue cup

faint musk of you within

back to ground I have gone

into murk of natal flesh

thrust of the child-wish

gone to ground for you I yearn

bound to you ever make return

Download the podcast

Jeneva Stone — poet, blogger, mother, federal employee, practical g/i nurse, interpreter of EOBs, queen of medical necessity letters, keeper of the family exchequer, unlicensed physical therapist, knowledgeable wheelchair mechanic — may also be found at Busily Seeking… Continual Change.

The Names of the Dead are Floated to Heaven, Gyeongju, South Korea

Click on image to view a larger version.

Robin Susanto lives in Vancouver, Canada. He takes photographs not as proof of having been, but as a way to slow down the act of seeing.

A quick visit to Joaquín’s, and a ceremony

from A Field Guide to Psychotropical Rainforest Birds

January 15, 2007

It was the weekend, and my young students had received a solid week of English, so I caught a ride down the river to go see Joaquín at his hut. A visitor was there, Jim Timothy from California. In his early 40s, he was slim and in very good shape. He had a receding hairline and a pencil-thin moustache like John Waters. He boasted of his ability to dance as many hours as boyfriends half his age. He described himself as an urban shaman and an organizer of rave parties with a spiritual focus.

“We always have a chill-out room,” he told me, “where there are always people on ecstasy having mellow conversations and giving each other backrubs. It’s better than having them out on the street drinking and fighting.”

He told me a dream in which he was in a natural history museum. In a dimly-lit corridor in the Egyptian section, he saw a diorama with a sphinx in it. She was alive and looking out at him through the glass. As he looked in her eyes he found that he was simultaneously himself and her, but more her than himself, because he was an emanation of her.

One day when he was a kid in Catholic school, he asked the priest, “We’re supposed to love our enemies, right?”

“That’s right.”

“And the devil is our enemy, so we’re supposed to love the devil, right?”

In another story he tells, he’s way out in the desert on an Indian reservation in the southwestern United States after having eaten peyote. He’s alone, naked, and playing a drum. A cloud of dust appears in the distance, gets closer. It’s from an approaching car. The car keeps getting closer and closer. It’s one of the tribal police cars. It drives up to him and stops. A big Indian cop wearing mirrored sunglasses gets out. Walks slowly up to him and says:

“You know you can’t do this.”

Jim says, “Yes.”

The cop says, “All right,” turns around, gets back in his car and drives away.

“Myths are computer chips,” Jim remarked in another conversation, “concentrated intelligence, survival information for hard times.”

I said, “One of my creative writing professors gave me a book of poems by the Serbian poet Vasko Popa called Homage to the Lame Wolf, named after an old Serbian tribal god. I found these poems astonishing because Popa was really operating from a different frame of reference than the other poets I were reading. The poems really were praise poems to this pagan god. I went to my professor and said this. He leaned back in his chair and said, ‘Vasko Popa knows a lot about wolves.’ I said, ‘Like what?’ My professor said, ‘And his grandmother knew even more.’ I said, ‘Like what?’ My professor said, ‘How to make love to them.’”

Jim replied, “This is a story about someone I don’t know well personally. We have a friend in common. This man works at an aquarium. They released one of their male sea lions back into the ocean. This man drives his car to the beach every Friday and picks up the sea lion and takes him home. He keeps him in the bathtub and feeds him fish, and they make love. On Sunday he returns him to the ocean.”

Joaquín made a ceremony with Jim and me. He chanted over cups of yagé and we drank and settled into hammocks and relaxed. For a long time we were quiet, listening to insects chittering and tweeting, and frogs honking and groaning, a thrilling music of wierdness. My mind took off and crash-landed in a realm of fragrant, burnt language, where mumbo jumbo, gibberish, and gobbledygook reigned.

Yagé’s not a bug or a slug, it’s a drug, but it’s way more than that, it’s a bat like a cat. It’s the distillation of the echo of gunflower elves. It’s green water in white rivers of blue oceans in the veins of bamboo. It’s subcutaneous calico lichen, vibrating neon gum that chews itself against the teeth of your mind, it’s an apparition of the face of Pan on a flower tortilla, it’s yellow blades of sunlight magnified by the black earth, orange skeins of spunlight delighting us through the perfect planet, red dreams of the One Light shaking us gently in the midnight morning saying “Hey, old friend, wake up, it’s time to BE, buddy. Time to be.” (Be, be, be, be, be, the verb reverberates off my lips.)

In a memory from my junior year in college, I’m lying on my back beneath a maple tree in October, blue sky above, and the intermittent cold breeze is shaking down the fantastic yellow red orange leaves, spinning against the sky as they fall. And I was thinking, “The tree is a natural clock that tells the time of the season. Each leaf that falls is another season second.”

What are the ramifications of this?

I chant silently, many times, the name of Avalokitesvara, the bodhisattva of compassion.

I’m in a sub-aquatic realm of blue and green… there’s something fierce about it… and it has many lizard eyes peering around. What I’m looking at is the fabric of lizard skins, and some gnomes in a workshop are cutting into it with instruments like cookie cutters, taking out lizard-shaped skins and sewing them onto lizard bodies. Of course lizards come into being through biological reproduction, I know that, but the natural process is mirrored by this supernatural one. This is simply how they fabricate lizards. The scene winks out and I’m in darkness again listening to the insect songs. Joaquín is snoring quietly.

I want to get rich selling fake wisdom, now that I know everything is fake. But then even my wealth will be fake, like Monopoly money. Sun, moon, and stars, all artificial—constructed like a stage set by elves attempting to convince us that this so-called reality is real. It’s built by the elves of Maya, by Maya’s elves, by My’selves—…. In this me-istic miasma of cells and selves, this self-same magnetic magma that is the body on yagé again. I’m in one of those places where everything one thinks of is true. So totally, undeniably accurate, and yet elsewhere it could be false. Truths have physical boundaries as much as countries have. I hold still, listening. Here the shamanic universe is infinitely vast and real. Elsewhere, it is not real, and other rules apply. And always, here, the crickets are singing, and my lungs are drinking this rich, clean air like a distillation of life itself.

More than yagé, I’m intoxicated by this divine, fragrant language of nature that keeps breathing within me and without me; I’m drunk on this plant animal language of squawks and whistles and humming and singing. An immense wave of nausea hits me, immediately followed by self-pity as I remember I will die someday, and then compassion as I remember everyone else will die someday too. With tears in my eyes I resign myself to pain, foreshadower of death.

And the crickets play their wordless songs with more intensity now, and I’m not sure whether the music is inside me or outside me, a language that reverberates through me until it’s all that I am…. And I stretch and shift, relieving a pressure in my back, and float once again in the delicate black water of the forest night, my head clear, resigned to nausea and to the lightness of my limbs as if I were the captain of a boat sailing through a calm sky of smoke high above a burning city. I’m cold, and I pull the light blanket up around my shoulders. What are Jim and Joaquín doing? Go slow, my soul. My stomach hurts; I listen. Joaquín is again snoring quietly.

I recall a line from an early explorer’s description of yagé customs: “Transported by the drink, the Indians dreamed a thousand absurdities and believed them as if they were true.” Yes, how compelling these absurdities are! It’s so easy to be transported by them! It’s like you never knew you were a sailboat, and then the wind comes, and off you go! We drink a thousand truths and believe them as if they were dreams. We dream of the myths of man and the dreams we learn to believe in when we’re dreamed into this world—night and day, something and nothing, here and there, now and then. We’re all tiny shoots of the human plant, reified and pulsating.

Dozens of gnomes march past me in the darkness carrying strange tools. Fireworks explode behind them. Transported by the drink, I’m borne into a 4th of July memory from when I was a kid. It’s 1974, I’m six years old, my mom and stepfather take me to the fireworks display at Veterans Park. They greet an aquaintance, Stacy, then move to an open space and spread out the secondhand quilt on which old automobiles are printed. My mom remarks about Stacy, “She’s high as a kite.” The display begins. I love the huge firecrackers booming in the drunken velvety summer sky, the whistling-screaming yellowy-white fireworks that corkscrew as they fall, the huge green plantlike ones that hold still in the high air with their smoke lit up by their fire, and the blue starlike ones that seem like love messages from outer space, while the spectators lie on blankets underneath, saying Oooooo! Ahhhhh! In 1996, I breathe deeply, living in two times, appreciating the old familiar glorious beauty.

Nausea.

Eagles and stars whirl around my vision, arrows and olive branches, stars and stripes, red, white and blue. This is part of my design. We’re woven into each other. This is part of my totem pole. America the beautiful.

Nausea, increasing the beauty of the visions. My eyes run with tears, red, white and blue.

Nearby, in his hammock, my fellow American Jim Timothy clears his throat and sings, his voice ringing out like a bell in the darkness:

The creator is our savior,

Hey ney yo wey,

The creator is our savior,

Hey ney yo wey.

Take care of us, take care of us,

Hey ney yo wey,

Take care of us, take care of us,

Hey ney yo wey.

The creator is our savior,

Hey ney yo wey,

The creator is our savior,

Hey ney yo wey.

Take pity on us, take pity on us,

Hey ney yo wey,

Take pity on us, take pity on us,

Hey ney yo wey.

The creator is our savior,

Hey ney yo wey,

The creator is our savior,

Hey ney yo wey.

Nathan Horowitz has three bright blue noses, six bright yellow tongues, 45 small, perfectly-shaped jet black ears, 95 hands, most of which are sleeping, and a long, long, long yellow and black stripy tail that wraps twice around the earth.

Faggot

I own the word

like you own your name,

let it roll off my tongue

and grate you like cheese.

Faggot.

Yes, I said it.

You’re not deaf.

I don’t stutter.

It’s the word you want

to use against me,

pour over my body

like boiling water.

Baby, I can stand the heat.

It’s a word

I once used.

Anthony. Faggot.

Brian. Faggot.

Lamar. Faggot.

It even tried to haunt:

Dustin. Faggot.

But I,

I deal the word

like a shark in Vegas.

Download the podcast

Dustin Brookshire is a poet and activist. He’s the founder of Project Verse, Quarrel, and Poetry Swap. Visit him at dbrookshire.blogspot.com.

The Atheist’s Art of Prayer

it was the day

my oldest friend left

for war

that i began learning

the atheist’s art

of prayer.

having no-one to speak to,

I don’t.

—no pleas,

no bargians

(my good behavior

for her life)

and no hope that I might be heard—

just the bright burning in my heart,

my hands clasped tight to contain it,

—while across the world

she speaks in tongues

and loses weight steadily, rapidly,

until in her photos I can see only her skeleton

peering through the face I used to know—

just my legs, buckled beneath me

and knees bruised

at the weight of it,

—no favors,

no reasoning,

and no hope that I might be heard—

just the insensate laws of cause

and effect, of motion and time and chance,

just the desperate,

helpless, and involuntary feeling

of please.

Caitlin Gildrien is a writer, farmer and sometime donut-walla in Middlebury, Vermont. She blogs at Up!

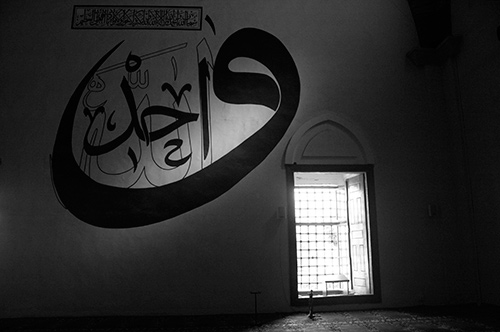

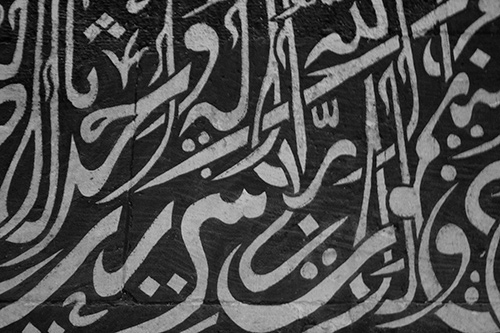

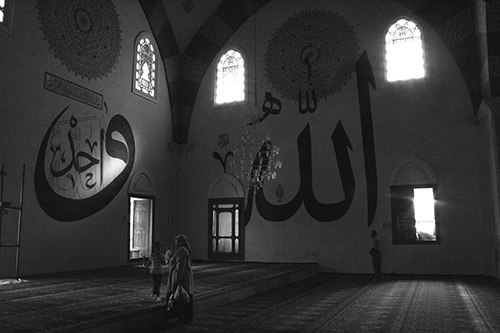

Eski Cami (Old Mosque)

These images are of calligraphic inscriptions on the walls and pillars of the Eski Cami (“Old Mosque”), a fifteenth-century Ottoman mosque in Edirne, Turkey. They consist of Qur’anic passages and of particular individual words freighted with religious force — Islamic calligraphy is both a devotional art form and a locus of apotropaic power. (Click on the photos to see larger versions.)

1. The word wahid (“one”) is superimposed over Allah (in outline only), so that together the composition can be read as “God is one.” 2. Hu, or “He,” meaning God. 3. Negative-space calligraphy (detail). 4. A doubled waw. The word wa means “and,” and in this context signifies union. 5. Mirror calligraphy on a pillar. 6. A large Allah (with praying man as punctuation mark).

Elizabeth Angell is a graduate student (among other things) in New York City. She blogs at verbal privilege.