Archive

Loquebantur variis linguis

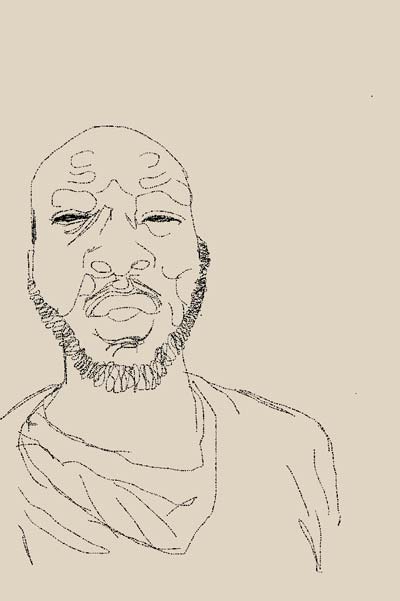

by Teju Cole

Thomas Tallis (1505-1585) wrote his setting of “Loquebantur variis linguis” according to the account of the Day of Pentecost given in the second chapter of the Book of Acts. When the Holy Spirit descended on the Apostles, they began to “speak with other tongues, as the spirit gave them utterance.”

I have drawn five self-portraits on the theme, imagining a choir composed of myself in multiplicate. But I wish to evoke, too, my experience of Pentecostal Christianity, which included speaking in tongues. The preaching I received, and which I passed on to others, was that the purpose of these untranslated and mystical utterances was to sidestep the Devil and to reach God directly.

These drawings were made on the iPhone using the Sketchbook app. I value this technique especially for its immediacy: the artist’s finger serves as the pencil.

Teju Cole (website) is a Nigerian-American novelist, photographer, and historian of art. He is the author of Open City, which will be published by Random House in February 2011.

Three Poems: Sculpting Texts Through Japanese Poetics

by Desmond Kon Zhicheng-Mingdé

spatialism is a haiku’s negative space

burnished and sliding

the same war is fought over

you, like other books

hobble at a time

backward, no nomenclature

in front, a sharp comet

straying into night

its flippant tail a languor

soft gold, winnowing

to say this trust is ashen

to gather grain —

otherwise everything goes

invalidates into a hush

a kuhi and their double slit

it’s the orb, lit green

striking self-help pebbles like

flints, their light fire

us at bering’s pond

upper crucks in a full fence

how long, this narrative thread?

how long a chronology?

it’s the orb north of

possibility —

itself ornate, warm

fine balustrade lined

it’s the corrosive

possibility of hope

of a leash, release

stone becoming rust, red dawn

as with recitation and the loss of a kuhi

this thieving of love

tightrope against what it means —

to visit the past

who is good; who wrong?

which brittle, yellowing build?

of old, bluing tarpaulin?

uniform as points, squares, lined

instincts and numbers primed too

quiet eyes like dark opal

their squircle an open seat

under chestnut shade

as with basho on his mat

there he lays, small, crouched

under a low-lying cave

its long, empty lake

praetoria of ruins gone

fingers curled into his palm

unfurling, unclenched —

tired hope for newer days

Author’s note: I am currently working on a project that experiments with and deconstructs the haiku/kuhi/senryu/tanka form, an enterprise of hybridity and transformation that treks the lines of interpretation and translation. (For more on spatialism, see the Wikipedia. –Ed.)

Desmond Kon Zhicheng-Mingdé has edited more than 10 books and co-produced 3 audio books, several pro bono for non-profit organizations. Trained in publishing at Stanford, with a theology masters in world religions from Harvard and fine arts masters in creative writing from Notre Dame, Desmond is a recipient of the Singapore Internationale Grant and Dr Hiew Siew Nam Academic Award. He has recent or forthcoming work in Copper Nickel, Fence, FuseLit, Nano Fiction, Oral Tradition, Red Lion Square, and Wag’s Revue. Desmond also works in clay, his commemorative pieces housed in museums and private collections in India, the Netherlands, the UK and the US.

Organ Donor

What you don’t know when you sign the release form is that death isn’t the permanent void that nonbelievers swear it is, nor is it the tranquil bliss that the enraptured would lead you to believe.

The truth, as always, is somewhere in the middle. The truth is, they are your organs for a reason that seems to transcend the biological. Your eyes may now be transmitting patterns of light to someone else’s brain, but they are still your ticket to the world and, frankly, I don’t like what I see.

What I’m seeing at the moment is an old man’s spotty hands forcing an orange tabby into a ratty carrier. Then there’s a swoosh-like blur, like watching a movie where the camera moves from place to place without cutting. Now I’m looking up at a young woman in a doorway, who’s squinting back tears. The old man’s hand comes into the frame and pats her on the arm. She steps back. There’s a one shot of the open-mouthed cry of the child in her arms. It goes dark. The old man has shut his eyes.

What the woman won’t see is the man placing the carrier tenderly on the lap of his gray-faced wife, his accomplice, and several blocks away, stopping the faded beige Toyota and switching the cat to the trunk with all the others. That’s the worst part, when the trunk opens and all those cats look up, their eyes dilated from darkness and fear, their mouths open in long yowls.

He’s good at this. He crams in the carrier, slams down the trunk, cranks up the radio and off they go.

There’s not a lot of money in selling cats for medical research or zoology classes. It’s hard work. He has to read all the classifieds, be the earliest caller, cover the whole city. It takes a lot of first class acting — first on the phone and then in person.

I know this because he reads from a script, how they need another cat because they’ve just lost Old Jake, or little Molly, “the sweetest calico you’ve ever seen.”

Every morning I follow his arthritic finger through the same sad stories: owner divorcing, dead, allergic, called up, moving overseas. Once upon a time, one of these was mine. Perhaps this is why this has happened to me. I was done with domesticity: husband, house, pets. The feeling was mutual. We ran an ad.

Free to good homes. Cats!

I used the bait word: free, the one that brings cat sellers right to your door like raw chicken brings gators out of a swamp. An old couple showed up, not my current couple, but another old couple, just as gray, just as quiet, and what do you know! They took both cats, “To keep them together.” How wonderful for big fluffy-gray Furangela and little white, part-Siamese Celandine, those best friends, who always slept together, curled light and dark, like Yin and Yang.

I never knew what I’d done until I woke up seeing my sin played out daily through the cat man’s corneas.

There are no accidents. There’s stupidity, there’s indifference and there’s redemption; and I’m done with the first two.

The cat seller and I meet in the mornings as he lifts his razor and stares into the mirror, into his eyes, my eyes.

Repent, I say, sensing some long ago Baptist in his lineage.

He stares for a moment, frozen, the razor ear-high, like maybe he hears me, like maybe I’ve become a faint ersatz conscience.

He says something, always the same thing, before jabbing one finger into the slack flesh of his face and pulling it taut over the cheekbone.

“A man’s gotta eat.” I think that’s what he says just before the razor goes to work.

Repent! Damn it! Repent.

Karen Stromberg is the proud companion of three cats, and would like to believe that fiction can somehow, somewhat, atone for past cruelties, even those performed in blatant ignorance. Other flash fiction can be found at qarrtsiluni and Pedestal Magazine.

Two from Rilke

translated by Florence Major

Porträt des Rainer Maria Rilke (1906) by Paula Modersohn-Becker (public domain image courtesy of the Wikimedia Commons)

HerbsttagHerr: es ist Zeit. Der Sommer war sehr gross.

Leg deinen Schatten auf die Sonnenuhren,

und auf den Fluren lass die Winde los.

Befiehl den letzten Fruchten voll zu sein;

gieb innen noch zwei sudlichere Tage,

drange sie zur Vollendung hin und jage

die letzte Susse in den schweren Wein.

Wer jetzt kein Haus hat, baut sich keines mehr.

Wer jetzt allein ist, wird es lange bleiben,

wird wachen, lesen, lange Briefe schreiben

und wird in den Alleen hin und her

unruhig wandern, wenn die Blatter treiben.

|

Autumn DayLord: Approach. Summer was everywhere,

Lay your dark hands across the sundials,

And across the open fields, free the coursing air.

Compel the last bounty holding to the vine:

Engorge. Permit two more balmy days’ reprieve,

Then press them to fulfillment, drive

Crowning fragrance into the heady wine.

Those without homes are too late.

Those without company will remain alone,

With books, with pen in hand till night is gone

Or searching, in the city’s corridors, a state

Of mind, as dead leaves when they blow.

|

Sonnets to Orpheus, II. XV

|

O Brunnen-Mund, du gebender, du Mund, der unerschöpflich Eines, Reines, spricht,– du, vor des Wassers fließendem Gesicht, marmorne Maske. Und im Hintergrund der Aquädukte Herkunft. Weither an vorüberfällt in das Gefäß davor. Ein Ohr der Erde. Nur mit sich allein |

O fountain mouth, unceasing passage of eternal oneness, inviolate, your speech flows through the marble mask to reach across distant peaks; a timeless message brought descending from distant graves. and falls arising in your marble bowl Earth, it is you who speaks, the ear the soul |

Translator’s note: These translations are not literal, but true to the meaning of the poems as I read and experienced them. I find that when translations are dogmatically literal, the poem often falls flat as the essence of what one feels on reading the poem is no longer in evidence. How words are spaced and arranged creates timing as in music. Compulsive rhyming in translations creates “dead meter,” and eludes the inner musical resonance of a poem that was rhymed in the original. Tricky stuff, but as the French say, à chacun son goût (to each his own taste).

Rainer Maria Rilke (1875-1926) was a Bohemian/Austrian poet and art critic, famed for his critique of Auguste Rodin. He is considered to be one of the greatest lyric poets of the German language and in the lexicon of poetry. He is best known for the Duino Elegies, the Sonnets to Orpheus and a semi-autographical prose work, The Notebooks of Malte Laurids Brigge.

Florence Major is an artist and poet born in Montreal, Quebec, and living in New York City. She has poems in The Chaffey Review and Cerise Press.

Qavak Songs

translated by Nancy Campbell

During the 1950s the oral historian Maliaraq Vebæk collected stories from elderly speakers of the Qavak dialect in the settlements of Cape Farewell, South Greenland. These settlements have subsequently been abandoned and the Qavak dialect has become extinct. Song is a central element of Greenlandic culture, and many of the storytellers enhanced their narratives with lyric interludes. The following songs record the voices of three legendary female characters. The original versions were performed by Juliane Mouritzen, Martin Mouritzen and Therkel Petersen.

Song of a female shaman known as ‘The Robber of Men’s Intestines’

Nailikkaataak sapangall, sapangallin

qivaaqinngivani sapangall

sapangallin

My cunt is hung,

hung with sea urchins,

My cunt bursts,

bursts with bladderwrack,

My cunt drips,

wet as a walrus snout.

My cunt is hungry.

Song of a wicked woman whose knowledge knew no limit

Uvijera kiillugu mikkissavan!

Kiillugu mikikkikki,

taana imaats qarsernun naqqulijukkumaarpan,

suuvalijukkumaarpan.

Kiillugu mikissavan, aaverling toqussuunga.

Tassa taamaaligima, toquguma

ummasunu pinaveerlinga mateernijarimaarparma.

Atamijaa ooqattaarimaarpan arn qisivanik.

Tass taamaatimik qarsilijern’jassuuti

taana naqqulijullugu, aataa taamaal

taasuminnga sakkeqalerivin toqukkumaarpan.

There’s only one way to kill your enemy:

You must bite my clit off, pull it inside out,

and use it as an arrowhead.

Yes! Bite off my clit and pull it inside out,

but I warn you, I will bleed to death.

Hurry up! Blunt but hard,

it is the best blade for killing.

When I have bled to death,

cover me, for beasts will want to eat me.

Hold the head in soft driftwood

and fletch the shaft with folds of skin.

Yes, that’s the arrow you need!

Only my weapon can kill your enemy.

Song of Ukuamaat of Kakilisat, the mother who left fox prints in the snow

Ernera, ernilijarsivara

tuugaaning assaqqoruteqanngitserng

Ernera ernilijarsivara

tuugaani nijaqorutaasaqanngitserng

nulijaaning assaarmigakku

taamalli ajunnguvarminaan.

My son, the man I made myself,

has no tattoos on his bony arms.

My son, the man I made myself,

will never wear an ivory crown.

I’ve stolen his only wife —

that’s no mean feat for an old crone!

Nancy Campbell (website) has published a number of artist’s books, the most recent being Dinner and a Rose, a multimedia response to Patricia Highsmith’s Ripley quartet of novels, commissioned by Poetry Beyond Text, which was produced in collaboration with the artist Sarah Bodman. The Night Hunter, forthcoming from Z’roah Press, was composed last winter while writer-in-residence at Upernavik Museum, Greenland: the most northern museum in the world.

To the Empathetic Poet from the Aphasic

I am rising from bed and calling it

vineyard, I am washing my face

and calling it my kitten, I am preparing

for the day which is my wife’s birthday,

and all I can say to her is three chairs

and a rousing crown of thorns, for she’s

a jolly good pharaoh, and she cries

and I cry too, telling her don’t cosset,

my lanyard, don’t captain and she’s not sure

if I mean stop crying or snap out of it.

I see the look in your eye, less

pitying than, really, admiring: such

freedom with the signifier, such constant

newness. Yes, yes, I can see you also know

this reaction is inappropriate, but still,

you indulge it. When I declare

the morning a boulder or the night

a ribbon studded with birds, you

delight in my poetic insight, as when

that child in the kindergarten class

(prompted, mind you) declared purple

to be a triangle. You claim to be

empathetic — get inside this, then.

I want to give my wife a kiss but have lost

the word. I call it a cargo and she cries

harder. It’s a matter of choice — if you, poet,

describe this vase as a book, very well,

convinced of your lyric authority, I’ll leaf

my mind’s eye through the pages

of its millefiori Venetian glass. But if I

call the vase a tree, it’s not my intention

to take you into a forest of redwoods

or to a willow beside a stream. I wanted

the vase. Yes, I’m making it new, but you,

you can name it — vase, wife, love — for all

you protest that you’re transcribing the unsayable.

Lisken Van Pelt Dus is a poet, teacher, and martial artist living in Pittsfield, Massachusetts. Her work can be found in Conduit, Main Street Rag, The South Carolina Review, upstreet, and other journals and anthologies, and has earned awards from The Comstock Review and Atlanta Review. Her chapbook, Everywhere at Once, was published by Pudding House Press in 2009.

wuirds/words

efter louis-ferdinand céline, via the Scots

|

at the stert o it aa there wis feelin the wuird wis-na there wi aa when ye kittle an amoeba a bairn greits oorsels juist the wuird is uggsome ti ventur sic is ill-faurt |

in the beginning there was sensation the word was not there at all when you tickle an amoeba a baby cries only us the word is disgusting to attempt it is ill-advised |

Author’s note: “wuirds/words” is a more or less straightforward found poem, taken from an interview given before his death (1961) by Louis-Ferdinand Céline, the whole of which appeared in another translation several years after the event (1964) in The Paris Review. The poem was originally rendered from the French into Scots, which I’ve subsequently translated into English. The poem itself speaks of the difficulty (impossibility?) of translating the subjective immediacy of phenomena into the social institution of language.

Andrew McCallum is a Scottish poet and scallywag with a distant background in European philosophy.

Call for Submissions: Translation

The editors invite submissions of poetry, short fiction, essays, visual poetry, photography, artwork and video for a translation-themed issue. The deadline is December 6 December 31, and the issue will begin to appear online after the New Year. All submissions must be made via qarrtsiluni’s new submissions manager.

In addition to work translated into English, we encourage a universal interpretation, including though not limited to movement between and within cultural fields and from signifier (code, symbol, signal) to signified (message, meaning, transcription). Translation being inherent in all acts of writing/reading, both semantic and non-verbal, we are interested in short, non-academic essays relevant to such readings and mis-readings. Please also send adaptations, definitions, conversions, and homophonic translations. Text submissions should not exceed three poems or short prose pieces, or some combination thereof, for a maximum of three single-spaced pages in .doc or .rtf format.

For translations, include originals, permission status, and a bio for the original author as well as your own. Translations from any language are welcome. We look forward to reading or viewing your work.

—Nick Admussen, Nathalie Boisard-Beudin, Nick Carbó, Alex Cigale, and Ayesha Saldanha

*

Nick Admussen is a Ph. D. candidate in Chinese literature at Princeton University, preparing a dissertation on contemporary Chinese prose poetry. His translations are forthcoming in Renditions, and have appeared in Cha magazine; his original poetry has appeared in magazines like the Boston Review and the Kenyon Review Online, and his first chapbook is due out this winter from Epiphany Editions.

Nathalie Boisard-Beudin is a middle aged French woman living in Rome, Italy. She has more hobbies than spare time, alas — reading, cooking, writing, painting and photography — so hopes that her technical colleagues at the European Space Agency will soon come up with a solution to that problem by stretching the fabric of time. Either that or send her up to write about the travels and trials of the International Space Station, the way this was done for the exploratory missions of old. Clearly the woman is a dreamer.

Nick Carbó is the author of El Grupo McDonald’s (1995), Secret Asian Man (2000), which won the Asian American Literary Award, and Andalusian Dawn (2004). He is the editor of three anthologies of Filipino literature: Pinoy Poetics (2004), Babaylan (2000), and Returning a Borrowed Tongue (1995).

Alex Cigale‘s poems recently appeared in The Cafe, Colorado, Global City, Green Mountains, and North American reviews, Gargoyle, Hanging Loose, Redactions, Tar River Poetry, 32 Poems, and Zoland Poetry, online in Contrary, Drunken Boat, H_ngm_n, McSweeney’s, and are forthcoming in Many Mountains Moving and St. Petersburg Review. His translations from the Russian can be found in Crossing Centuries: the New Generation in Russian Poetry, in The Manhattan, St. Ann’s, and Yellow Medicine reviews, online in OffCourse, Danse Macabre and Fiera Lingue, and forthcoming in Crab Creek Review and Modern Poetry in Translation. He was born in Chernovsty, Ukraine and lives in New York City.

Ayesha Saldanha is a writer and translator based in Bahrain. She has translated a wide range of Bahraini fiction and poetry. Some of her translations of Gulf poets will appear in Gathering the Tide: An Anthology of Contemporary Arabian Gulf Poetry to be published by Garnet Publishing/Ithaca Press in 2011. She blogs as Bint Battuta.

Editors’ names link to their work in qarrtsiluni, where applicable.

*

This issue is a first for us in three respects: it will represent qarrtsiluni’s very first foray into publishing translations; it’s the first we’ve tried to work with a team of more than two issue editors; and it’s our first experiment with a real submissions management system. If you’ve submitted to other publications that use the same system, Submishmash, you’ll need to log in with the same username and password. Otherwise, you’ll create a new account as part of the submission process. Most of our general guidelines remain the same, and are included on the submissions page.

Please let us know via email (qarrtsiluni [at] gmail.com) if you experience any problems with the new system. We’re cautiously optimistic that it will help us keep better track of submissions, and we’re pretty certain that contributors will appreciate the ability to log on and see how their submissions are doing, but we’ll see how it goes. For more about the service, check out this interview with one of the lead developers.

We hope this call for submissions will prompt some imaginative responses from past contributors and expose us to the work of new authors and artists as well. Best of luck to all.

—Beth and Dave