Archive

Mictlantecuhtli, 2010

Click on image for a larger view

Joaquin Ramon Herrera is a writer, illustrator, director, cinematographer and artist-activist. He blogs at The Unapologetic Mexican and you can read more bio here. Check out Scary: A Book of Horrible Things for Kids on Amazon.

The Monsters Receive Their Briefing on Millennium Park

Vampires should be concerned

about the convention of crosses

beamed above the broad expanse

of the Great Lawn. Even if you can

arrive undetected, your pale faces

will be unreflected in the Cloud

Gate, every tourist turning from

his own convex visage to point

and stare then break branches from

the dense arbor nearby, scrape them

across the concrete to fashion stakes.

Werewolves should take caution

while viewing the following slides;

please shield the eyes of younger

lycanthropes. First are the wings

of the Pritzker Pavilion, rising like

a broken ribcage, bones curling out

from the impact of a blast to the chest.

Very disturbing. Then that giant bean,

(see warning to vampires) poised

at the park’s edge like a silver bullet,

just waiting to be fired across the lake

at the eye of a full, white moon.

Frankenstein, you should be all right.

Tall, bulky men abound in Chicago.

But please be careful in the Lurie Garden,

the path of wildflowers high and filled

with small children who frighten easily.

You know what happened the last time

you picked daisies with a little girl. So

stay to the west, watch the photos

on the Crown Fountain, all those faces

smiling, sans stitches. Pull your scarf

tighter against the strong lake wind.

Not a soul will ever notice your bolts.

Donna Vorreyer’s list of classics includes her family, Diet Coke, Thin Mint Girl Scout Cookies, and Star Wars movies. She lives in the Chicago area, and you can visit her and her work at her website or on her blog.

Onion

The onion is pregnant with disappointment,

carrying her squat body to the market,

shedding skin like brown veils,

She has miscarried—

weaving a long strand of pearl-shaped tears

for the loss she still carries

like a phantom memory,

the shape of the embryo, hallow as a conch shell—

She passes a church without mumbling prayers

believing prayers are not heard after all,

Her brown sadness is a skirt touching the ground,

Her husband abandoned her when she needed him most,

absent as prayers, a need that has to get out,

empty as a bottomless well.

If there is anything that removes her pain,

she cannot find it

in the dusty streets

the color of her wrinkles.

Martin Willitts Jr. has had poems recently in Blue Fifth, Parting Gifts, Storm at Galesburg and other stories (anthology), The Centrifugal Eye, Quiddity, and others. He has been nominated for four Pushcart Awards. His second full length book of poetry is The Hummingbird (March Street Press, 2009). His eleventh chapbook is Baskets of Tomorrow (Flutter Press, 2009), and he has two forthcoming chapbooks, True Simplicity (Poets Wear Prada Press, 2010) and The Girl Who Sang Forth Horses (Pudding House Publications, 2010).

Dream in Five Acts

by Karl Elder

In a bar the bartender claims is frequented by Clint Eastwood I am in the army on a weekend pass in my civies. It’s dark in here, really dark, it’s 2 p.m., and I have been walking for hours in the California sun without something like the sunglasses I now have on and, as I sip straight gin, no matter where I swivel nor how I turn I can’t see behind.

“This is one dark bar room,” I say, pointing at the mirror. I say, “Where does he sit? ”

The bartender says, “What?”

“Eastwood,” I say, “where does he sit?”

“He sits where you’re sitting, only he’s taller.”

The way the bartender says taller I know it is the end of act one.

Act two is the same scene only the bartender is a woman, and taller. Because I am in the army I’ve never seen a woman in my life and I am taller. It is a good thing I have sunglasses on. I cannot believe I am married and I am not here with her, my wife, that is, not the bartender. When we were on vacation in San Francisco a year ago I was with her, my wife, that is, not the bartender. Here I am in the army in Monterey where a glance is a stare. It must be the atmosphere, spare, cavernous, in fact, where you are served gin over diamonds you can crunch and they disappear.

“I hear Clint Eastwood frequents here,” I tell her.

I’m in the army and it’s act three, California, a cave in the city of Monterey.

“You could be him,” she says, “for all I know. The guy wears a disguise.”

In comes another customer looking like Abraham Lincoln, who orders an Olympia and walks it up the far end of the bar and thus toward my chair. I’m in the army and I’m not surprised he knows, though lately in different mirrors I never look the same way twice.

I tell him so in the fourth act. It is my affliction, I say. Abe is so honest, so innocent, I think he believes me as my fists fence each other with little plastic swords that held plump, stuffed olives, reminding me of eyes that never blink.

“No, really,” I wink, “I’m in Monterey in a cave because I shaved off my mustache in the army up the road at Ord because my C.O. made me. I’m married so don’t try to hit on me and that goes for you too, Missy.”

Abe orders me an Olympia.

By act five, arms draped over each other’s shoulders, Abe is calling me Clint. I’ve got a make up artist so good I wear a Karl Elder suit. Abe’s ears and beard are both on the bar, and absent the get-up he looks a lot like the guy in the mirror. It is February, 1972, and I’m writing a Valentine to my wife in Illinois on a cocktail napkin in a cave the bartender on a earlier shift claims is frequented by me, Clint Eastwood, who is in the army on a weekend pass. It’s dark in here and Abe Lincoln who looks more like me every minute is my understudy in a dream about Monterey and wants to know the secret of life.

“Kid,” I say, “you’re barking up the wrong tree.”

Karl Elder is Lakeland College’s Fessler Professor of Creative Writing and Poet in Residence. Among his honors are a Pushcart Prize; the Chad Walsh, Lorine Niedecker, and Lucien Stryk Awards; and two appearances in The Best American Poetry. His most recent collection is Gilgamesh at the Bellagio from The National Poetry Review Award Book Series.

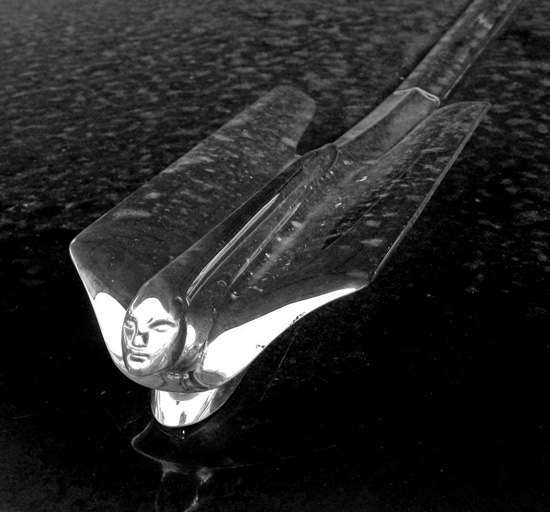

Cadillac Gargoyle

by Steve Wing

Click on image to see a larger version.

Steve Wing (PBase gallery) is a visual artist and writer whose work reflects his appreciation for the extraordinary in ordinary days and places. He lives in Florida, where he takes dawn photos on his way to work in an academic institution. He’s a regular contributor to qarrtsiluni, as well as to BluePrintReview, where he has a bio page with links to some of his other publications.

Pay Asclepius a Cock

by Eric Burke

My father wasn’t really sick. He was only pretending. (Though his need to pretend might be a sickness. At least, that’s what he liked to think.) He was very tired.

My mother was melodramatic. She said my father was melodramatic. I never really believed her.

My sister left home early to marry a man who looked like he knew what he wanted.

I never left home. I make my own bed. I lie in it, as comfortable as anyone ever really is.

Eric Burke works as a computer programmer in Columbus, Ohio. Recent work can be found in elimae, Pank, Right Hand Pointing, decomP, Otoliths, and Heron. Work is forthcoming in A cappella Zoo. He blogs at Anomalocrinus Incurvus.

Wounded Man at War in the Metro Père-Lachaise

by Martha Deed

“Too sad to sing” the older Auden wrote to whom

as un mutilé de guerre took my seat on the Metro Père-Lachaise

and glared at me, jealous of my youth and two fine legs. “Why

are you here?” he demanded to know. “He’s buried in Kirchstetten,

Lower Austria, I believe. That last poetry reading killed him on the spot,

and no funeral procession through those streets could bring him back

to life: A poet’s worst nightmare to be killed by one of his own poems,

I believe, and as for me — just look at this scarred face, this empty sleeve —

uglier than anyone inside those gates if you chose to dig one up.

‘La cité des morts’ some call it — a name that could apply to all of Paris

if you ask me — since the great De Gaulle resigned in ’69 — some say

because of mai soixante-huit. He’s not here, you know, but keeps his peace

in Colombey-les-deux-Eglises.” The wounded man gazed down,

then up again with moistened eyes: “They didn’t like him much, you know,”

he whispered in the humming train: “your FDR and the cigar – Churchill…

They even tried to throw him out.” He raised his voice in raspy rage.

“Can you imagine? Our Gallic Rooster, our premier resister?

denied his place by johnny-come-latelies who never fought

a war? We stood them down: the meddlers. You won’t find them

buried here — your Gertrude Stein, the garden poet, they let her in.

Pennsylvanian born; Parisienne by choice, she knew of war first-hand,

rejected the repetition of it, lacked the foreign leaders’ chutzpah,

and knew the strength of modesty: ‘I have lived half my life in Paris,

not the half that made me but the half in which I made what I made’

she said.” He shifted in his seat as the train entered Republique,

then quickly gained the open doors. “You resemble her,” he said.

“But thinner.”

Martha Deed (website, blog) is a retired psychologist who makes trouble with poetry inspired by crises and other mishaps around her house on the Erie Canal in North Tonawanda, NY. Recent publications include her chapbooks, The Lost Shoe (publisher’s page, video trailer), 65 x 65 and #9, and an e-book, Intersections, a 20-day journey of the unexpected. Recent poetry publications include: Iowa Review on the Web (with Millie Niss), Unlikelystories.org, Poemeleon, New Verse News, Dudley Review, Helix, The Buffalo News and many others.

The Lears at Home

Regan broke things

by accident, Goneril

broke them on purpose, and Cordelia

was careful (careful!) and saved them, milky china girl

holding the does, thumbsized miniature piano

with gilt keys and a rose. That was before

they were fiends, when Goneril, if she wasn’t

winning, would only tear up the Monopoly money, saying

“It isn’t real money, anyway.” And how they would nudge

her, kick her, actually, at the end, saying

“Get up!” and “You’re not really dead,” which was less

consolation than you might suppose, as the

whole idea of us all being actors

when looked at closely

is less than reassuring, implying

that simply getting up and on cancels dread,

as if there were no politics or cruelty

in theater. Anyway, for Cordelia

acting the role was just like

playing the part, what with not having any good lines

or kisses and having to be banished

and then blindfolded for Gloucester and be pushed down

and be Kent in the stocks (though at least she got to yowl

for that one)–it’s no wonder she took up

tumbling to get attention. And Goneril would make them all

get off the phone, that hot tense silence

to listen for Edmund’s calls. She’d throw herself

at the cold whorled elements, ocean, storm,

hoping they’d cool her down. At first she’d hoped

he’d be like that, but soon saw he was too

sizzling, viperish, and Regan never told her

he could come on differently,

though pinching at odd moments.

Now they’ve learned to pause

for commercials. You can tell Goneril’s passions

by her coiffure, square cut, solid as

villainy, dits of liner like hard girls

in the fifties, her emphasis

soothing in its relentlessness.

Regan’s a pale poufy blond who talks kind, leaves you tired.

They talk about the old man,

how he runs up his phone bill, flies with his

cronies to Vegas, how they’re going to have to

put him in a home. Some smarmy practitioner

comes on, folks call in

aging parent stories. But it’s hard to keep

to this rhythm,

once you’ve seen that this play

is written and put on

by three girls, sisters at the edge

of puberty: the sex all hard hugs and partings, the vagueness

about strategics and real land values, small kings

schoolgirls in drag.

And the father, Regan trying to learn

to be Goneril, saying

lines you might invent for an absent man.

Monica Raymond won the Castillo Prize in political theater for her play The Owl Girl, which is about two families in an unnamed Middle Eastern country who both have keys to the same house. She was a Jerome Fellow for 2008-09 at the Playwrights’ Center in Minneapolis, among many other honors and awards. Her poetry has been published in the Colorado Review, the Iowa Review, and the Village Voice, and her work has been selected for publication by every pair of qarrtsiluni editors for eleven issues in a row now.

matisse two

by bl pawelek

bl pawelek (website) has been to a million places in life and has forgotten most of them. But he is here now and trying.

Sometimes I Miss the Old Jealous Goddesses

by Deb Scott

Your cold force

whistles through frothy

cracks and if I had one

one of those infrared-reading

gadgets all the seams

would glow

hot

like an enthusiastic

Hercules hiding his children

from fertile madness

Questions of fidelity

render fat

from stones raised

in a complicated family

no simple begats from began

blunt those elites

who wonder is it nurture

or nature shouldered between

strong thighs the size of earnest

temple columns Frozen deities

take the brunt of heredity

smudge the edges of this still life

A caesura reveals more about how

shadows cast

than progeny can set sundered limbs

Deb Scott lives in Portland, Oregon. She blogs at Stoney Moss and was one of the folks behind Read Write Poem. These days she and friends are ring-leaders at Big Tent Poetry, an online poetry prompt site. Deb’s poetry, prose and photography are published or forthcoming in a number of journals, including Ouroboros Review and tiny words. (A complete list is here.)