Archive

Keats in America; Ode to Wilderness

by Alex Cigale

No mythic grange of crag in snow and horn

Nor forests thick beyond numbering nor

Beasts uncountable dense upon the plain

Nor unspoiled terrain of river and glade

For not even the habitation of awe

That grandest scree of sublime solemnity

Has ‘scaped the ken of the learned geographer —

In leaden skies aligned on Canyon’s deep

As atmospheric growling scours the night

And astral satellites hurtling by sweep

The mottled towers in invisible light

In bottomless oceans scuffle machines

That bathe the abyss in resonants of sound

Etching an exquisite topography —

The most remote top of butte and plateau

Scarred by boot track and route littered with

Candy wrappers film canisters spent batteries

Where no road leads in but many peter out:

Wilderness; where I am and you aren’t.

Alex Cigale’s poems recently appeared in the Colorado, Global City, Tampa, Green Mountains, and North American Reviews, Drunken Boat, Hanging Loose, McSweeney’s, Redactions, Tar River Poetry, and 32 Poems. His translations from the Russian can be found in Crossing Centuries: the New Generation in Russian Poetry, Cimarron Review, Literary Imagination, Modern Poetry in Translation, PEN America, Brooklyn Rail InTranslation, The Manhattan Review, and St. Ann’s Review. He is currently teaching at the American University of Central Asia in Bishkek, Kyrgyzstan.

Keeping Things Real

after Mark Strand

In a field

I’m not one of

the cows.

This is

always the case.

For all x not equal to me

I am not x.

When I walk

I don’t stay still

and always

the air moves in

since gas is

compressible.

We all have reasons

for moving.

I’ve been

kicked out by my girlfriend.

Zackary Sholem Berger (website) is a Baltimore-based poet and translator writing in Yiddish and English. His first book of poetry came out in 2011. Titled Not in the Same Breath, it’s 1/3 Yiddish, 1/3 English, and 2/3 pretty pictures, and can be purchased here.

The Fugitive Light

Auroral nights, the moon a flick of peel,

When I am dyed in blush of northern lights . . .

The waving colors steal

Across the sky, turn flights

Of sea-green souls to rose, as hard to vase

As flower she who faded in my arms.

What’s light-struck flits, as a sunset raises

Its glowing bars to fence another day

Away from us; as blazes

Die to coal; as one ray

Illuminates in memory your face,

Then darkens like an hour of grave alarms.

In dreams you come to me and take my hand,

And nothing fades or flees when you are there.

On waking, I am unmanned,

Sundering and care

My lot; yet I will bear the daily grace

Of bread and voice recalled and sun that warms.

Note: “The Fugitive Light” pays homage to the young Richard Wilbur of The Beautiful Changes and Other Poems (1947). However, the subject matter of the death of the beloved comes from the elder Mr. Wilbur and his poem “The House” (Anterooms, 2010), evoking his late wife and the longing that comes after death parts those who had the fortune of a happy marriage. Likewise I have ended with the simplicity of his late poems.

Just published is Marly Youmans’s ninth book, A Death at the White Camellia Orphanage (The Ferrol Sams Award of Mercer University Press, 2012. Chapter one of the novel can be read at Scribd). Her most recent book of poems is The Throne of Psyche, also from Mercer (2011). Forthcoming books of poetry and fiction include the long poem Thaliad from Beth Adams’ Phoenicia Publishing in Montreal.

Old Torso at the City Museum

(After Rilke’s Archaic Torso of Apollo)

by Paul Dickey

I do not know, sir, what happened to his head—

the eyes were turned to cash like market fruit?

And now the old hump glows in schemes of bread

to fool the pawnster who’d select profit

to art and light. If not, would I alone

be standing here and ogling the rock’s breast,

checking out the hips and thighs of yeah, a stone,

suppressing snickers at the dude at rest?

From what I see, the relic is damaged goods,

not worth a patron’s call to wake the mayor,

and not a thing they’d toss a dude in jail for.

Though shysters can bust you out with lies or knife,

these eyes know you. I slide to home and hoods,

before the heat arrives to change my life.

Paul Dickey’s full length poetry manuscript, They Say This is How Death Came Into the World, was published by Mayapple Press in 2011. His poetry has appeared recently in Verse Daily, Rattle, Sentence: A Journal of Prose Poetics, Mid-American Review, Midwest Quarterly, Crab Orchard Review and online at Linebreak, among other online and print publications. A poetry chapbook, What Wisconsin Took, was published by The Parallel Press in 2006. See his webpage for more information.

Two Poems After Hesiod

by Brett Foster

1. Advice to a Brother

It’s wise for us to marry at thirty,

and you’re not far off the mark. So realize,

a maiden like this is what you should choose.

Men want her because they can teach her good

manners, but wait till she’s four years full grown.

Timeliness is best. Perses, don’t be fooled,

don’t marry what will make your neighbors laugh.

One rule: nothing’s better than a good wife.

A bad wife’s fireless heat will dry you out.

Any brother can tell his brother that.

2. Portrait of a Maiden

Boreas, rising over open water,

bends to the earth the tips of sapling fir,

sets the forest splintering by his wrath.

Neither oxen hides nor fine-haired goatskin

prevent beasts being cut through with shivers.

A matted, sheep-wool pelt can keep him out.

Though he levels the elderly like reeds,

the maiden’s skin still glistens, unassailed:

face fire-radiant behind shelter walls,

yet untouched by golden Aphrodite’s

mysteries, she learns to be beautiful,

as her mother sitting beside her was.

She bathes, dries her body carefully,

anoints it with oil, then to bed. Hazards

rage beyond the dark, inner chamber.

Brett Foster’s first book of poetry, The Garbage Eater, was published last year by Triquarterly Books / Northwestern University Press. Writing of his has recently appeared in Ascent, Atlanta Review, Crab Orchard Review, IMAGE, Kenyon Review, Pleiades, Poet Lore, and Seattle Review. Poems are forthcoming in Salamander, Spoon River Poetry Review, and Theodate.

Bring Your Own Water

after Richard Siken

the sign outside the bar in Tucson says,

so we do. we bring our own water

to a failing river. to a drowning

dog. we bring our flimsy shoes

to a road acned with potholes,

we throw them in and leave

them there. when it’s time to leave,

we take our water. the bartender says

it’s not that easy. shows us the potholes

in the floor filling with dirty water.

suddenly it’s my fault. our shoes

sit in the road, in the holes. drowning

isn’t what it seems to be. a drowning

man walks out of the bathroom. leave

him alone, you say. but his shoes

are untied. I’m not your father, he says.

there’s a dog in the street lapping water

with his enormous red tongue. potholes

start forming on the bar, potholes

big enough to for a dog to lie drowning

in. we’re looking for our water,

they told us to bring it, told us to leave

and it doesn’t make sense, I say,

why did we abandon our shoes

in the street, what can we do without shoes,

where is the river. I take a pothole

from the bar and sip, the bartender says

last call. the bartender says drowning

is an outside job. he wants us to leave

but you’re just getting started. river water

starts filling up the lightbulbs. river water

pours down the bar back mirror. our shoes

ride in on water. on a dog’s back. we leave

the bartender pushing napkins into potholes,

all the barstools unpinning from the drowning

floor. on the way out, we hear the man say

he can’t find his shoes. you see me and say

we all get what we deserve, leave me drowning

in a street of water, your mouth, a perfect pothole.

Marty McConnell (website) has placed work in numerous anthologies and journals including Crab Orchard, Salt Hill Review, Beloit Poetry Journal, Drunken Boat, Rattle, Rattapallax, Booth Magazine, Fourteen Hills, Thirteenth Moon, Boxcar Poetry Review, Pedestal, 2River View, and A Face to Meet the Faces: An Anthology of Contemporary Persona Poetry. She received her MFA from Sarah Lawrence College and has been a featured reader at numerous literary festivals including the Geraldine R. Dodge Poetry Festival, Connecticut Poetry Festival, and the Palm Beach Poetry Festival. After ten years in New York City, during which she co-founded the literary nonprofit the louderARTS Project and co-curated its renowned reading series, she recently returned to Chicago to establish its sister organization, Vox Ferus.

Not an Ode to Oppen

let’s keep it simple

an ode is for the high

the ethereal

the elevation of something

but being interested in essential present aliveness

in the not high

in the unelevated

we cannot then assume the heavens

there is no firmament

no sky of blue Madonna

it is unattainable or rather, it doesn‘t exist.

here on the ground

the framework holds

because words are carefully selected

like objects in a rich man’s public space

and meant to mean because

we were depending on them to save us

but forget all that.

November is here and there are still roses

pink roses made of many, many petals

in the grim parking lot at Walgreens

pink riding above November’s slow gray skies.

Cecilia Pinto’s work appeared previously in qarrtsiluni’s collaboration issue, Mutating the Signature, and has appeared in various other journals. She notes that “Not an Ode to Oppen” is “both an imitation and a rejection of the work of poet George Oppen.”

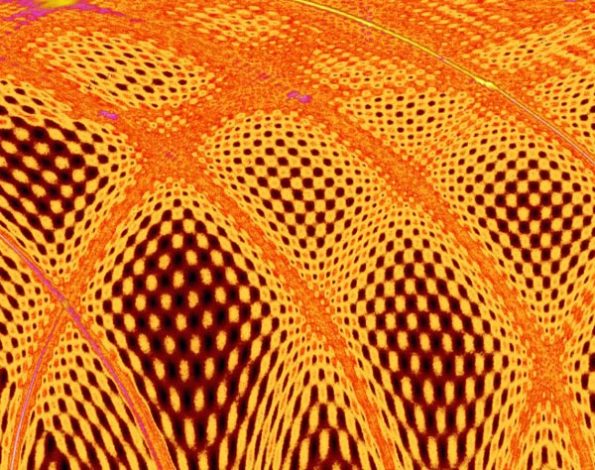

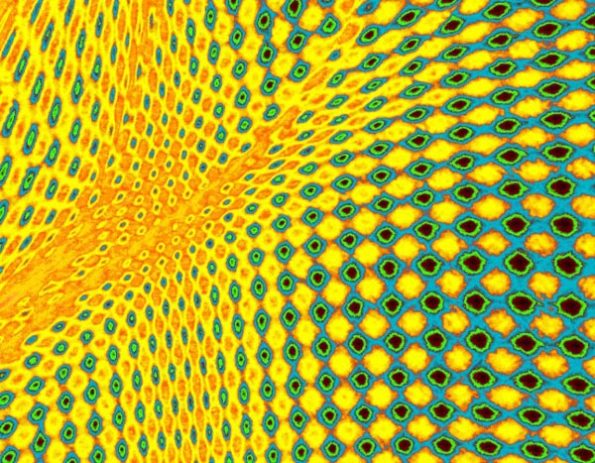

Homage to Victor Vasarely

by Steve Wing

rectilinear fatigue (click on images to see larger versions)

In homage to Victor Vasarely, a pioneer of what became known as Op Art. This genre brought unique perceptual energy to art, often utilizing geometric shapes and shading to create illusions of movement and depth that are almost vertigo-inducing.

*

Steve Wing lives in Florida and has been a frequent contributor to qarrtsiluni. More about him can be found here.

False at First Light

by Kerry Harwin

With thanks to Ernest Hemingway for teaching me that even a lie ought to have truth at its core.

I wished that Amar wasn’t the way that he was. He was fine friend and not a bad man. But he was a difficult man to be friends with. I wished he didn’t need his whisky and soda and cola at ten in the morning, and I wished that once he got tight he didn’t need so badly to be so damn helpful, especially when he was trying to help me with women. His drunk instinct was infallibly disastrous no matter whom I was chasing.

Amar lacked the forethought to buy a ticket for the plane or the train, so he came on the bus. He smelled of whisky and dust and benson and hedges and of twenty hours of hard road. He joined us both, me and Jeremy, at the cafe table; outside for that brief moment in a New Delhi October when a man in shirtsleeves can leave the comfort of four walls and climate control.

Jeremy was something like Amar with money, a European upbringing, and self control. Or, at least, enough self control to wait until the afternoon for his wine, and to go home when he was too drunk for anything else. But even his control made you depressed, because it seemed to spring from an awareness that things weren’t going to get any better in any case.

We were fortunate that evening. Our night train and coming journey gave us something to talk about. And so we weren’t forced to listen to Jeremy, oblivious to the impact his words had on Amar, plaintively moan about the poor mental constitution of the Indian man and the many ways in which the subcontinent was doomed. After four years spent as a banker in Bombay, Jeremy had developed a detailed taxonomy of Indian faults. Having exhausted all his complaints about whatever establishment we were drinking or eating in, or the hotel he last stayed in, he would inevitably find a way to tie this to some shortcoming in the Indian character. And so, as he held forth on the flaws of Indian bankers, the Indian service industry, Indian men, Indian women, Indian families, Indian Muslims, Indian Christians, and Indian Hindus, you could see the toll it took on his Indian acquaintances. The toll it was taking on Amar right now. For Jeremy was cursed with the special kind of oblivion that comes from a very human settling; a settling into resignation or despair accompanied by an awareness of the improbability of amelioration. That obliviousness left him blind to fact that the only Indians he knew were the rich and travelled sort who spent much of their time engaged in the same nature of complaint. He was even more thoroughly blind to the fact that those Indians had earned by birth a right to complain about their nation that is rarely endowed upon the foreign born.

Nor were we subjected to the flow of words on love and suffering that were the frequent mainstay of Amar’s conversation. Amar was in love with Shirley and Shirley was engaged to someone else and Shirley was a bitch and Amar a masochist and the combination is a dangerous one. Shirley was the too common type of woman who would mete out just enough crumbs of tenderness to keep Amar constantly pleading for more. Amar was the kind of man who lacked the spine to tell her what she ought to do with them.

Amar had left his fiancé for Shirley and Shirley had left Amar because he wasn’t the type of husband that her parents had in mind. She wasn’t a woman you’d want to know; she had the body and the temperament of every entitled rich girl any man has ever tried to avoid, without the face to make up for all that. So Shirley slept with Amar’s friend, and then left him after he was so foolish as to fall in love with her. And then she slept with the new fiancé her parents had found for her. And then with all three of them on alternating days and then only with the fiancé again until it was settled and he had won.

These days Amar sits on the floor and watches bad television and drinks whisky until the whisky comes out of his eyes and he asks why she doesn’t love him anymore. And I tell him that she’s an awful shrew and he’s better drunk and lonely and without her and have another Vat 69, sport. Watching a drunk man sob is an unpleasant but sometimes necessary task. But a blubbering drunk defending his tormentor isn’t something a man ought to witness. Both the cryer and the watcher will have to acknowledge it or ignore it the next day, and neither way is any good. The drunk can choose to forget, at least, or pretend that he has anyway.

So there’s no choice. I can either give the usual platitudes or give a hard smack followed by another glass. One has a duty to a drunk and broken friend, and duty is a simple, wonderful thing. It obliges without need to reflect or consider; nothing is easier for a man.

But none of that mattered. We were the table, and we were outside, and it was night. And the air was just beginning to turn to what passes for winter in New Delhi and it was neither warm nor cold. Our train was late and our dinner was long since finished, but we lingered over bottles of wine that would be regretted by all but Jeremy when the check arrived and we hoped in vain that he would take the bill.

He often did, for he liked being needed, as all of us do.

“We don’t want to miss the train.”

“There’s time for one more glass.”

“Yes. But quickly,” Jeremy ruled, “I hate to rush in the station.”

The train to Udaipur bears little mention. It was hot and it was crowded for a great many hours and then we were there. And moments later, we were gone, the road scarred Indica carrying us away from the urban desolation of the desert city, thronged with man and beast and horns and dust and shit, towards another altogether more empty desolation.

In India, things are false at first light. The falseness burns in the afternoon sun and is scoured with dust and sand but doesn’t change. It is only after nightfall that things become true. True not because anything has changed within them, but because you have worn yourself down. You have given so much time and effort to teasing the real from the false that both have lost their meaning. There is no more false; it has been overtaken by a truth born of nothing more than fatigue and acceptance. At night you know that everything is the way that it is and that how it is is how it ought to be.

Note: This is an extract from a longer work.

Kerry Harwin has been living in India — Bombay, Calcutta, and Delhi — for almost four years. He works in an office during the day, plays music for drunk people in night clubs on the weekends, and occasionally writes on culture and lifestyle, travel, and energy policy in several outlets of little significance. The most pressing thing he would like to know about you is what song you’d like to listen to while you blast off into outer space, should you ever find yourself in a space shuttle. He would choose “Glass Dance” by The Faint.